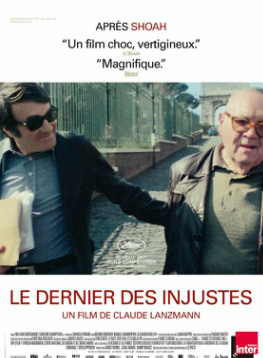

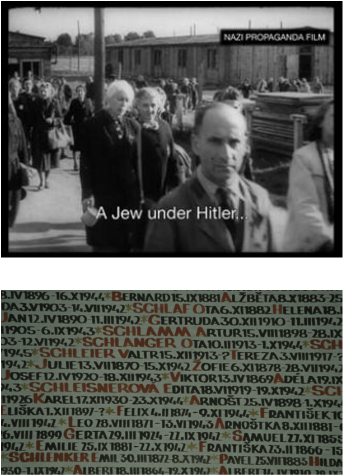

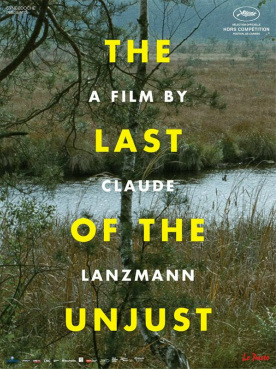

On March 9, the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies co-sponsored a screening and discussion of Claude Lanzmann's new film The Last of the Unjust with the Art Theater Coop and the Champaign-Urbana Jewish Federation. You can also read Prof. Laurie Johnson's response to the screening here. By Brett Ashley Kaplan The title of Lanzmann’s newest film inverts the title of an important 1959 novel by André Schwartz-Bart, Le derniers des justes (The Last of the Just); it is the principal subject of the film, Benjamin Murmelstein (1905-1989), a Rabbi and Elder of the Jewish Community in Vienna (1938-1943) and Theresienstadt (1944-1945) who coins the title by telling us that he is not exactly the last of the unjust but rather the last of the guards. This tension between a self-representation as unjust and as a guardian of the imperiled Jews of Vienna and beyond marks Murmelstein’s testimony. Before seeing the film I had expected that Lanzmann would push Murmelstein more vociferously about the question that always arises in the context of the Jewish community leaders: the continuum between victimization and perpetration that structurally located them. Instead, Lanzmann frames the testimony of Murmelstein, which he filmed in Rome in 1975 but chose not to include in his vast Holocaust documentary Shoah (1985), within a larger narrative about Theresienstadt, about how place and memory work together and against each other, and about the masking practices of Nazi propaganda. Throughout the film, Lanzmann forever presses on the absence of the traces in the gritty landscapes on which his unwavering gaze falls; he “ruingazes” the lost past.[i]  Lanzmann begins The Last of the Unjust by echoing Shoah. Having himself filmed on a train platform in Bohušovice, the stop for Theresienstadt, we are set up to be reminded of Shoah, not only because trains conjure deportations but also because he stylistically replicates the long pans of and sounds of trains and landscapes characteristic of the earlier film. When Lanzmann tells us that Theresienstadt had the “le pire” conditions he obviously knows exactly the enormous weight that this term carries; “le pire” (the worst) features in many, many French memoirs, novels, testimonies, and theory as shorthand for the extermination of European Jewry. The closing of the film makes a complete circle; whereas in the opening it is Lanzmann, alone, with memories of Shoah, by the close two middle aged survivors, Lanzmann, now joined by Murmelstein, whom he sympathetically terms a “tiger,” walk towards the camera with the Arch of Titus framing them, but then they turn and walk back towards the arch, which rises into the frame as they approach, thus structurally reversing Hitler’s triumphant take over of Paris with all its attendant scenes of Nazis marching through l’Arc de Triomphe. The triumph over forgetting, Lanzmann seems to be arguing here, may not take the bombastic form one might expect; it may be a talking cure.  Der Führer Schenkt den Juden eine Stadt Theresienstadt was an idyllic spot which then became an “apocalyptic vision;” in order to convey this apocalypse, and in stark contrast to Shoah, Lanzmann here uses archival footage: several stills and also long excerpts from the Nazi propaganda film made inside Terezin in order to “fool” the Red Cross and therefore the world into believing that the Jews of Europe were merely being held in lovely, music and art filled conditions and not exterminated. Theresienstadt was indeed a model ghetto; but when using the archival footage from the propaganda film Lanzmann inserts “mise-en-scène Nazie” over the left-hand of each frame thus foregrounding the fakeness of the film and never once letting us be sucked into the propaganda about the ghetto. Lanzmann shows images from some of the many artists incarcerated in Theresienstadt including Bedrich Fritta, who was born in Višnová, Bohemia in 1906 and killed at Auschwitz in 1944. From 17 May until 29 September, 2013, Fritta’s drawings were on display at the Jewish Museum, Berlin. In describing the exhibit, the Museum locates subterfuge as the center of Fritta’s deportation from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. Along with Leo Haas and others, these artists, “secretly used the studio materials to record the misery of everyday ghetto life” and for this they were deported. Haas survived and after the war adopted Fritta’s son Thomáš.[ii] Later in the film when Lanzmann is in Prague at the Pinkas Synagogue he gazes at the memorial there—a memorial designed between 1954 and 1959 but closed for several years due to the poor physical state of the building. The memorial lists the names of the 77, 297 victims from Bohemia and Moravia.[iii] While the camera pans these names Lanzmann tells us that they are so crowded together as to resist legibility; but then the camera settles on the name of Bedrich Fritta thus bringing us back to the images at the beginning and reminding us of the aesthetic revolution that lead to Fritta’s death. He focuses on an image of Fritta’s name to hone in on one person and to combat the sense of the endless, endless wash of the undifferentiated dead.  The Back of Murmelstein’s Head The first image of Murmelstein is an extremely uncomfortable, odd, prolonged close up of the back of his head; throughout the course of the interviews Lanzmann’s camera man will focus in closely on Murmelstein’s face—especially during the scenes filmed in a small room as opposed to those shot in the open on Murmelstein’s pleasant balcony; in many of these close-ups Lanzmann and/or the camera man are clearly visibly reflected in Murmelstein’s coke-bottle glasses thus always reminding us of the constructed nature even of documentaries. As Lilya Kaganovsky argues, this is Lanzmann’s “way of trying to get ‘in’ to understand Benjamin Murmelstein, and in the end that fails; the glasses work the same way, instead of offering us a 'window to the soul' (as eyes are supposed to do), his glasses just reflect back ourselves.”[iv] Murmelstein tells us his field is mythology and indeed throughout the film he compares himself to a number of literary and mythological figures—beginning with Orpheus—and tells us that like his mythological forbear he did not want to look back into the past but felt compelled to do so; he also compares himself to Scheherazade from A Thousand and One Nights in that they are both compelled to ceaselessly tell stories. He had been silent for thirty years and when Lanzmann asks him why that was the case he replies, “other people talked too much.” In 1961 Murmelstein published Terezin; il ghetto-modello di Eichmann (Bologna: Capelli) but had not spoken about Theresienstadt publicly until his 1975 interview with Lanzmann. Murmelstein is the only Jewish Elder of Theresienstadt to have survived the war. When he first gave testimony—and he volunteered to do so as he stresses that he had been issued a diplomatic Red Cross passport and thus could, at the end of the war, have escaped but instead he decided to stay in Czechoslovakia and face trial—when he first testified he was asked, abruptly, “how did you survive?”  Murmelstein compares himself to other elders, including Chaim Rumkowski ([1877-1944], Chairman of the Judenrat in the Lodz ghetto) who, according to Murmelstein, understood himself as a tragio-comic figure. He felt mocked by the Nazis, and, from the Nazi perspective all the Jewish leaders were marionettes in their games. Rumkowski portrayed himself as a marionette but Murmelstein does not want to see himself this way. Murmelstein was the third and final Elder of Theresienstadt, after Jacob Edelstein (1903-1944) and Paul Epstein (1902-1944).[v] Murmelstein was faced with an impossible choice between taking advantage of the betterments offered by the very project—ultimately to serve Nazi propaganda--of the embellishment of the ghetto for the film or being shot like Edelstein or hung like Eppstein. Murmelstein insists that his choice to work with the Nazis ultimately helped many of those incarcerated. At one point, Murmelstein discovers lice and typhus and he decides that the only effective way to get the population of Theresienstadt to agree to be inoculated would be to only issue daily rations of food to those who had a stamped inoculation card; on the one hand, this could be read as refusing food to the hungry, but on the other hand this could be read as saving the population of the ghetto from the epidemic. After the war, Murmelstein was accused of attempting to starve the inhabitants; he defended himself by stating that he was trying to save them through these harsh measures and describes himself several times as someone who chose pragmatic if harsh measures. He sees himself as having always made the best choices in an impossible situation; the film does not close down our opinion but rather leaves open the decision as to whether we agree with this self-assessment. One of the important historical contributions to the film is that Murmelstein discounts Arendt’s famous theory of the “banality of evil” by finding from his first-hand experience that, rather than an automaton-bureaucrat pushing papers that murdered hundreds of thousands of people, Eichmann was there on Kristallnacht (10 November 1938), with a crowbar, smashing synagogues. Lanzmann, a little incredulous, presses Murmelstein to clarify that Eichmann himself had a crowbar and Murmelstein emphatically confirms. Murmelstein insists that “demon” would be a much more appropriate word for Eichmann than “banal.” Landscapes The international scope of the genocide and those who are left to remember is underscored by the landscape switching between Bohušovice, Rome, Jerusalem, Vienna, Prague, Theresienstadt, Nisko, Zarzcezce. Quite abruptly and without any explanation the scenes often shift while the testimony of Murmelstein continues; for example, just after explaining that the Nazis saw the Jewish leaders as marionettes, Lanzmann moves to contemporary Jerusalem and features a long series of shots from a car driving down a picturesque road with iconic Israeli landscapes unfurling behind. Then, again abruptly, there is way too much lush, green to be in Israel and after several seconds of panning over all this lushness a caption appears explaining that these are the vineyards outside Vienna. Testimony from 1975 plays over the landscape of 2013. In the opening text of the film Lanzmann tells us that Murmelstein has a “pure love” for Israel but has never gone there; at the close of the film Lanzmann asks why he has never traveled there and Murmelstein replies that the Israelis could not try him properly. Israel appears then, as “pure love” as a series of landscapes shot from a moving car, as the place that did not try Eichmann properly, and as the natural response when presented with evidence of genocide. This last point happens when Lanzmann, regarding one of the memorial plaques entitled the Gedenkweg [path of memory/chemin de la pensée] in Vienna happens upon six non-Jewish Viennese who are taking the memory walk and who, once they have read the plaque, unfurl an Israeli flag.[vi] Murmelstein tells us that he was issued two certificates for Israel in 1939 which he gave to a student instead of taking his wife and child to Palestine because he informs us that he needed to stay and the student and his wife did emigrate; Murmelstein wonders whether he did the right thing in giving the certificates away and forever forgoing this landscape of pure, unrequited, love. Lanzmann lingers over a long take of a cantor singing first the Kol Nidre and then the Kaddish for all the Jews killed during the war. This is the only music in the entire film. The cantor himself then becomes another landscape over which Lanzmann projects his discourse; in this case he describes a memorial for the 65,000 names of the Viennese Jews murdered in the war which evokes Maya Lin’s Vietnam War memorial even though the practice of the listing of the names long predated this sculpture.  Lanzmann then opens a new chapter; it is almost a reprisal of the beginning because he again focuses in on a train station, a place, a landscape but now instead of Bohušovice it is Nisko and Lanzmann has his own argument to make about the progress of the transformation from Nisko to Auschwitz; throughout this section Lanzmann reads from white sheaves of paper that we must assume are his narrative about how places figure in the history of genocide. Nisko was a space where, in competition with Madagascar, there was going to be a Jewish reservation—and the subtitles call this space a “reservation” which of course cannot help but recall the American Indian Reservations. There is a landscape that we see over and over again of a river shadowed by a glorious sunset; this seems to be somewhere in or near Nisko which Lanzmann has told us is between the Bug and San rivers so this river is likely one of these; but at the same time there is a deliberate confusion between Madagascar and Nisko as examples of Nazi masking of extermination as deportations, relocations, and protectorates. Lanzmann pointedly lists “Madagascar, Nisko, Theresienstadt, Auschwitz” and thus argues that an initial drive towards expulsion turns into genocide. Murmelstein insists that Madagascar was all along “camouflage” for the final solution. It was a mask says Lanzmann, yes, a mask Murmelstein agrees. Zarcezce is a place where 13 rudimentary huts were built which were to be the beginning of this Jewish reservation but obviously this never materialized in full; Lanzmann tells us that there are ordinary things in this town, even a nightclub. Indeed, the next shot lingers on two words separated by two different awnings the one on the right says “Night” and the other on the left “Club.” In English. All of a sudden we are in Prague, it’s the iconic shot of the Charles Bridge, tourists and people walking over it; a long take of an upright church contrasted sharply with the tumbled down cemetery in Prague. The Golem Synagogue is, Lanzmann tells us, a “bijou absolut.”  Unforgettable Beauty Lanzmann reminds us that people wanted to believe that Theresienstadt could be a place that was not like the rest of the death camps. Then we are suddenly inside the remains of the ghetto, on the very spot where the events Murmelstein has been testifying about unfolded. And then Lanzmann describes a long scene of hanging. At one point it was decided by the Nazi administration that anyone who committed a tiny infraction would be hung. Edelstein was then the Jewish Elder in charge and he was given a choice: if you do not find a hangman, you will be hung. And so, Edelstein, who Lanzmann describes as a “brave Zionist” set out to find a hangman. First, he asked three butchers who all said no; and then he found a certain Fischer who worked in a morgue and he decided that he would offer himself as the hangman. Lanzmann stands there in the space where the people were hung and he looks up at the sky, which is visible through the decaying remains of the corrugated ceiling, he looks down at the weeds and he describes it as a “lieu de mort.” It is also a place of “inoubliable beauté,” unforgettable beauty. [i] For more on ruingazing see: Julia Hell, "Katechon: Carl Schmitt's Imperial Theology and the Ruins of the Future." Germanic Review 84:4 (Fall 2009), 283-326.

[ii] http://www.jmberlin.de/fritta/en/biographie.php [iii] http://www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/a-ex-pinkas.htm [iv] Personal email, 11 March 2014. [v] http://www.bterezin.org.il/120869/Ghetto-Leadership [vi] http://www.viennareview.net/news/special-report/path-of-memory

0 Comments

By Laurie Johnson On March 9, the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies co-sponsored a screening and discussion of Claude Lanzmann's new film The Last of the Unjust with the Art Theater Co-op and the Champaign-Urbana Jewish Federation. Here is a response to the film and discussion by Prof. Laurie Johnson. Another response to the film by Prof. Brett Kaplan will appear in a few days. Claude Lanzmann is not known for avoiding filmmaking challenges, but at the beginning of The Last of the Unjust he states that he “backed away from the difficulties” of integrating footage from extensive interviews with Benjamin Murmelstein into the documentary tour de force Shoah (1985). The March 9 screening of Unjust at the Art Theater in Champaign, Illinois prompted the question of just why Lanzmann might have found this particular footage difficult to use as part of Shoah: was Murmelstein, a Viennese rabbi who became the third and final Jewish Elder in Theresienstadt/Terezín, too ambiguous of a figure, positioned between victims and perpetrators in a way the earlier film would have found tough to address? The interviews Lanzmann conducted with Murmelstein in Rome in 1975 (when Murmelstein was 70), lengthy segments of which are reproduced in Unjust, do not make that impression. While Murmelstein does not portray himself as a victim, he also never blurs the line between himself and Nazi officials such as Adolf Eichmann, who ordered Murmelstein to research “methods of emigration” beginning in Vienna in 1938, and with whom Murmelstein was forced to work for seven years. Murmelstein’s lengthy descriptions of Eichmann provide a more nuanced and chilling picture than is available even in the most recent scholarship on Nazi perpetrators. Murmelstein’s characterization of Eichmann as a “demon” is fleshed out with too much specific detail to seem melodramatic. Lanzmann challenges Murmelstein frequently during their Rome discussions, accusing him at one point of a strange lack of emotion, given the nature of his testimony. But Lanzmann never substantially questions Murmelstein’s depiction of Eichmann, though he does press for details, particularly about Eichmann’s involvement in Kristallnacht. By enabling a clear and sharp distinction between Murmelstein and Eichmann, Lanzmann renders the lines between victim and perpetrator more rather than less distinct. While Murmelstein indeed does not seem emotionally vulnerable in the interviews, he is passionate and energetic, an affect that matches his vibrant descriptive phrases. His characterization of eastern Europe, and Poland in particular, as a place of “absolute indeterminacy” starkly conveys a sense of why the Nazis could capitalize on Western ignorance about this area in order to do whatever they wanted, without witnesses or investigations. While listening to this description, we see present-day images of spaces in Poland and the Czech Republic where camps were erected, now empty again—their present emptiness again “hides” the fact of what happened there. For instance, Lanzmann visits Nisko (Poland, then part of the German Generalgouvernement), where Eichmann had deported over 3,000 Jews, a significant moment in the trajectory that culminated in the Final Solution, but today empty and largely forgotten. It is not the images of the deserted spaces, but rather Lanzmann’s and Murmelstein’s narration, that reveals the truth—a truth that often has left no physical trace.  In the first Rome interview segment shown in Unjust, Murmelstein emphasizes the fact that the absence of Jews in Europe has enormous consequences for substantial parts of the globe. In segments shot in the present, Lanzmann visits the Memorial to the 80,000 Jewish Victims of the Holocaust from Bohemia and Moravia at the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague, as well the Old Jewish Cemetery in the same city. The thousands of names inscribed on the synagogue walls, and the crowded stones in the cemetery may initially make an anonymous and overwhelming impression, but it is precisely then that we can access something like a feeling for the absence Murmelstein invokes. The walls filled with names and the jumble of stones do not impel us (at least not when viewed all at once, as a whole) to remember specific people or moments—they are not markers of lost presences so much as of an utter absence. Similarly, the deserted streets of Theresienstadt, the “Kleine Festung” prison on the opposite side of the Ohre River from the ghetto, and other sites Lanzmann visits, empty now again, underscore the collective absence of all who could have been. There is no escape from this absence, even in anti-Semitic fantasy: when Murmelstein speaks about the plan concocted at the 1936 Diet of Warsaw to deport Jews to Madagascar, he emphasizes that for the Nazis Madagascar was a trick, a double-mask that hid the truth of Theresienstadt, even as Theresienstadt in turn hid the fact of Auschwitz.  Murmelstein casts himself as a modern-day Scheherazade, who survived the Shoah in part due to his ability to tell stories—and who, he implies, still survives (in 1975) in order to continue storytelling. Telling his own story is part of this as well. When explaining why he did not leave Vienna in the late 1930s when he had the chance (he in fact returned from London voluntarily), Murmelstein acknowledges a certain “thirst for adventure” and sense of mission. He reminds Lanzmann that he was also young and healthy then, and simply felt less vulnerable. Murmelstein also relays part of the story of his own relationship to power, saying: “Everyone picked to do something has the feeling he is the right one to do it.” Near the end of the film he asserts that an “Elder of the Jews can be condemned. In fact, he must be condemned. But he can’t be judged, because one cannot take his place.” Of course, Murmelstein did take the place of not one but two previous, murdered Jewish Elders, Jacob Edelstein and Paul Eppstein (and Eppstein had taken the place of Edelstein). Yet Murmelstein convincingly asserts his unique place in a world that counted on his replaceability. In the present-day sequences in Unjust, Lanzmann implicitly supports Murmelstein’s insistence that no one can take the place of a Jewish Elder: when the filmmaker stands in places Murmelstein has been, from Vienna to Theresienstadt, he is representing Murmelstein’s stories in the present and thereby paradoxically reaffirming his own inability to take the last Elder’s place. Lanzmann describes himself as “haunted” by Murmelstein, but when he returns to the Kleine Festung or to Nisko, he haunts these spaces himself—while he is there, they cannot mask the past; while he is filming, Murmelstein’s stories will be told, and the “unjust” will receive a kind of justice. The screening of Unjust at the Art Theater on March 9 was followed by a panel and general discussion. Michael Rothberg (English, Illinois) remarked that although the film is much shorter than Shoah, its length (approx. 220 minutes) is nevertheless reminiscent of the earlier film; the viewer needs to make a substantial time commitment and really go through an experience with the filmmaker. However, Rothberg noted that Unjust uses filmic time differently than Shoah: Lanzmann narrates for about twenty minutes in the present (in French) before cutting back to the 1975 interviews (in German); although we saw Lanzmann age throughout the twelve-year period in which Shoah was filmed, the discrepancy in his age between 1975 and 2013 is of course considerably greater. While Shoah was “always in the present tense” (Rothberg quoting Lanzmann), emphasizing the speech of the living and eschewing footage and archival images from the past, Unjust makes use not only of the 1975 interviews, but of drawings and film from the 1940s. For instance, there is an extended sequence from the Nazi propaganda film made in Theresienstadt. As a sharp contrast, we see drawings made by inhabitants of the ghetto, most of whom perished.  In addition to delineating differences between the two Lanzmann films, Rothberg also reminded the audience of the differences between Lanzmann’s persona as a filmmaker as opposed to as a public figure. When interviewing and filming other scenes in his documentaries, Lanzmann tends to be very focused on detail and on the minutiae of history. But when he speaks as a public figure, he addresses the Holocaust in a mode perhaps more sacral than historiographic. Brett Kaplan (Comparative and World Literature, Illinois) also considered similarities and differences between The Last of the Unjust and Shoah, remarking on Lanzmann’s use of train and railroad images and sounds in both films. She then wondered what Lanzmann’s reliance on images of landscapes and spaces in the present reveals or conceals about what happened there—spaces where, as mentioned above, events related to the Shoah took place, but which are now largely empty and silent. While the spaces themselves do not signify the specific past events, in the film they become invested with the meaning Lanzmann assigns to them. Kaplan also remarked on the use of names, monuments, and signs in the film (markers in the present), and found these as noteworthy as Lanzmann’s deployment of images from the past. And, she emphasized the differences in how Murmelstein spoke in interview footage filmed on an outdoor balcony in Rome as opposed to his somewhat more intense affect in conversations with Lanzmann in a small interior space. Although Unjust consists in large part of verbal interactions, Kaplan focused on the way visual cues transmit meaning.  Lilya Kaganovsky (Comparative and World Literature and Slavic, Illinois) returned to the question of why the Murmelstein interviews were not included in Shoah. She commented on the fact that Unjust in general breaks with many of the filmic strategies Lanzmann used in Shoah, introducing footage from very different time periods, using archival material and images of memorials, and including Lanzmann himself as a type of character, in the present-day scenes. Even though the Murmelstein interviews were conducted during the making of Shoah, they end up contributing to a very different kind of film. But both are documentaries, and Kaganovsky remarked that the documentary’s “pursuit of truth” permits all kinds of strategies: interviews, re-enactments, the use of archival images, and the re-inhabiting of spaces that no longer signify what happened there in the past. Audience members joined in the discussion, observing that the text shown at the beginning of the film is essentially Lanzmann’s way of telling us what to think, as it assures us that Murmelstein does not lie. Perhaps, though, Lanzmann means that Murmelstein himself does not think of what he is saying as a lie. Some wondered if the fact that Murmelstein had been through these memories so many times (albeit never on camera, prior to 1975) meant that he necessarily lost a certain degree of emotional reactivity. Others thought that while Hannah Arendt’s assessment of Adolf Eichmann has been considered outdated for some time, Murmelstein’s pointed, detailed recollections will make it difficult to rely on the phrase “banality of evil” in an unquestioning way in the future. The past is indeed gone—and, as one audience member pointed out, what use is memory? since, implicitly, memories often cannot be verified definitively, and since remembering does not necessarily prevent atrocities. The word “last” in the title The Last of the Unjust may indicate that the specific history that Benjamin Murmelstein represents is really over. But the documentary, while signaling memory’s end, also preserves its ghostly traces. This film ensures that although the last person who remembers what really happened is gone, the haunting will continue. |

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed