|

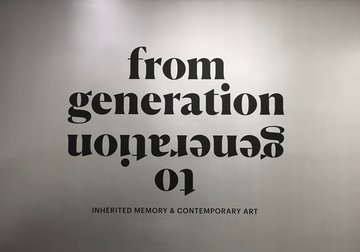

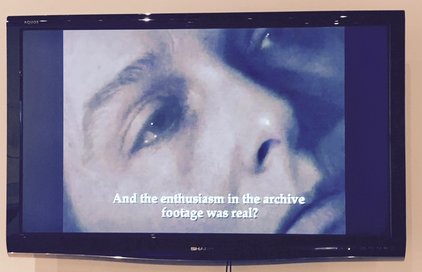

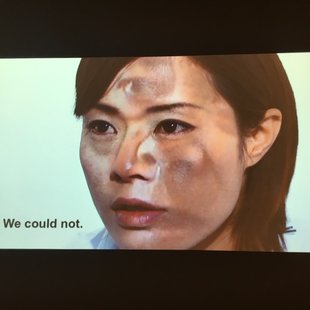

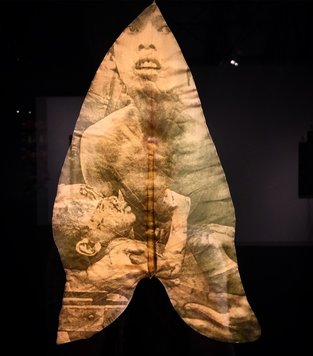

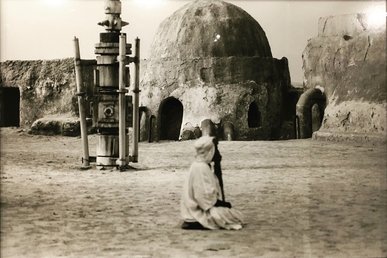

Recently, my husband momentarily misplaced his wedding ring. While this might seem to be a commonplace, yet anxiety-inducing event, it created a unique moment of mnemonic crisis for us: my husband’s wedding band originally belonged to my grandfather, a metallurgist who forged the ring himself and engraved it with my grandmother’s initials and their wedding date in 1936, shortly after they fled Germany. As we searched for the ring we tried to remember what the engraving read; despite studying the words for years, we could not remember the exact arrangement of initials and dates. We wondered how we could replace the ring, its engraving, as well as its scratches and dents, the evidence it bore of the lives of generations of wearers. We found the ring, but the anxiety of loss lingers, urging me to reexamine my own relationship to the indexicality and transmission of generational memory and weigh what those of us in the second and third generation removed from trauma owe to our ancestors and to the past.  This personal meditation on generational memory actually began several weeks ago when I visited the exhibit “From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memories and Contemporary Art” at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. According to the curators, the title embraces “l’dor vador—the call to pass tradition from one generation to another,”[1] fitting the museum’s focus on representing contemporary Jewish culture. The exhibition employs Marianne Hirsch’s foundational concept of “postmemory” to thematically organize pieces from twenty-three international artists as they depict memories they have not experienced, but inherited. According to Hirsch, “postmemory describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma or transformation of those who came before—to events that they ‘remember’ only by means of stories, images and behaviors among which they grew up. But these events were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.”[2] The exhibit thus asks us to consider how various familial and cultural pasts are transmitted to these artists and how they choose to represent, as Hirsch describes, these “belated, temporally, and qualitatively removed” memories.  Anri Sala’s "Intervista" (1998) Anri Sala’s "Intervista" (1998) Despite this generational focus, only some of the works are primarily concerned with familial memories, those passed down from parents to children through not only overt methods such as storytelling and photographs, but also more subtle silences and affects. One of the pieces that specifically focuses on parental transmission is Anri Sala’s Intervista (Finding the Words) (1998), where the artist attempts to reconstruct the lost vocal track of his mother’s speech to Albania’s Communist Youth Alliance, a recreation that his mother cannot recognize or remember almost thirty years later. Other than these intimate family portraits, most of the exhibit is concerned with larger cultural forces that shape generational memory, even within the family. This is not at odds with postmemory, as Hirsch argues, “Family life, even in its most intimate moments, is imbricated in a collective imaginary shaped by a shared archive of stories and images, by public fantasies and projections,” mediations that become especially important after traumatic events that resist comprehension and need multiple forms of repetition to work through, especially amongst families who do not speak openly about such pasts. Though trauma and transformation are often presented as breaks in the continuum between past and present, the “post” in “postmemory,” Hirsch writes, “reflects an uneasy oscillation between continuity and rupture,” where the past and present exist in uneasy yet entangled tension. Art is thus a valuable medium for working through difficult and transformative pasts while navigating the familial and the cultural, the personal and the collective, to see how the past resonates today, shaping our hopes for the future.  Reflected in "Amelia Falling" (2014) Reflected in "Amelia Falling" (2014) The exhibition is loosely broken up into three parts: personal, collective, and future memories, although these scales are often blurred. In “personal memories,” intimate and often painful moments in the lives of individuals are represented, encouraging us to consider not only the artists’ relationship to their subjects, but ours as well. In Amelia Falling (2014), artist Hank Willis Thomas prints a photograph of Civil Rights activist Amelia Boynton after she was beaten unconscious in the Selma, Alabama march of 1965 by State Troopers on a reflective mirror.[3] Thomas focuses on Boynton in mid-faint as she is supported by two marchers, allowing viewers to see themselves reflected above the distressed trio. Placing the viewer in this event collapses the distinction between the personal and the collective, the past and present, asking us to empathize with Boynton’s personal suffering while connecting this difficult historical moment to current instances of police brutality.  Detail from "Chac-Mool" (2015) Detail from "Chac-Mool" (2015) In a similar act of intimate mediation of inter-generational transmission, Nao Bustamante’s installation Chac-Mool (2015) transmits the memories of Leandra Becerra Lumbreras, who at a purported 127 years old, was the last surviving soldadera, or female fighter in the Mexican Revolution. Sitting on a stool in front of a makeshift wooden video player, we are invited to peer into a viewfinder and listen on headphones to Lumbreras beat out a revolutionary anthem on her drum. Thus the originary intimate process of intergenerational memory transfer between the artist and her subject is replicated through Chac-Mool, where the personal stories and defiant affect of Lumbreras are passed on to us, the museum visitors. The endurance of Lumbreras’s tune is reiterated in Bustamante’s other piece, Kevlar Fighting Costumes (2015), where the signature dresses of the soldaderas are reproduced in bullet-proof Kevlar. This retroactive effort to protect the female soldaderas is also an attempt to preserve their legacy and empower new generations of feminists and female freedom fighters.  Still from "Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat" (2009) Still from "Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat" (2009) This theme of testimony eliciting intergenerational empathetic attachment is reiterated in Chickako Yamashiro’s powerful video, Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat (2009), where a survivor of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 tells his story through the mouth of the young artist. As his voice speaks through her moving lips, the artist begins to cry in an extreme display of empathetic connection to her subject, and later, when the ghostly image of the survivor is projected over the artist’s own face, there is almost a collapse between artist and subject. However, the artist stops short of appropriating the survivor’s testimony, closing her mouth as he recounts the violent death of his family. While this work questions the limits of empathy cultivated through posttraumatic testimony, it also brings up a disturbing dimension of postmemory: “if we adopt the transformative or traumatic experiences of others as ones we might ourselves have lived through… can we do so without imitating or over-identifying with them?” Hirsch asks. Your Voice Came Through My Throat seems to skirt the delicate border between empathy and appropriation, but it remains a powerful moment of intergenerational memory transfer.  "Holding 2" (2009) "Holding 2" (2009) In line with new directions in memory studies, two works examine the environment as it shapes personal and collective memories of trauma. In one of the exhibition’s most striking works, Vietnamese artist Bihn Danh prints images from the Vietnam War on leaves using a photosynthetic process in a series called "Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War" (2005-2009). Danh juxtaposes three leaves bearing images of American soldiers during combat with four leaves depicting the devastation of the war, where wounded children are held by visibly traumatized adults. By bringing together the natural, the leaves and images of familial intimacies, with the unnatural mechanisms and trauma of war, Danh asks us to confront the process of memory as both an organic and mediated process. The diasporic biography of the artist intensifies the wartime trauma depicted on the leaves; Danh and his family left Vietnam as refugees shortly after he was born and he has been unable to imaginatively return to his homeland as it existed for his parents, before the conflict and their resulting exile. His multiple traumatic displacements are reflected in his choice of organic medium: though they are preserved in resin, eventually these delicate leaf prints will fade and completely disintegrate, demonstrating the limited longevity of postmemory.  Image from Series "Bomb Ponds" (2009) Image from Series "Bomb Ponds" (2009) Vandy Rattana also explores the aftermath of the Vietnam War through his photographic series, Bomb Ponds (2009), which document the bomb craters littering the Cambodian countryside left in the aftermath of American bombing raids starting in 1969. The craters remain today, some filled with toxic water, as an enduring and inescapable environmental reminder of the war, asking us to consider how the environment continues to shape the lives and memories of multiple generations by bearing the scars of traumatic pasts.  "Every World's a Stage" (2012) "Every World's a Stage" (2012) Given the gravity of the exhibition, I originally had difficulty navigating the levity of the “future memory” section, where artists playfully stretch memory to its imaginative limits, at times abandoning the generational theme organizing the rest of the exhibit. Contrasting the traumatic landscapes of Bomb Ponds with Rä di Martino’s photographic series Every World’s a Stage (Beggar in the Ruins of Star Wars) (2012), which features a Tunisian beggar amongst abandoned Star Wars sets, potentially trivializes the earlier photographs. While di Martino’s point is that these artificial environments take on new memories for different populations—that those who use the sets today as dwellings do so without knowledge of the pop-culture phenomenon that is Star Wars—the fictional conflict of the films pales in comparison to the environmental imprint of the war represented in Bomb Ponds.  Detail "Kandor 17" (2007) Detail "Kandor 17" (2007) Similarly, Mike Kelley’s installation Kandor 17 (2007), which imagines Superman as a diasporic subject, despite its melancholic undertones, seems almost trivial compared to the actual diasporic experiences of Danh. While many of us know that Superman’s journey to Earth was precipitated by the destruction of his home planet, in a later series Krypton’s capital, Kandor, survives, albeit in shrunken form. Kandor 17 thus laments Superman’s inability to return to his home even as he is tasked with preserving the miniaturized city and its inhabitants under a bell jar displayed in his Fortress of Solitude. On the surface, Kandor 17’s bright color palate and fanciful recreation of a fictional universe seems to undermine the gravity of diasporic memory presented elsewhere in the exhibit, however, when one remembers that Jewish immigrants fueled the early comic book industry, we begin to see the gravity, and yes, solitude, behind the playful exterior of Kelley’s installation.[4] Fitting with the museum’s larger mission to present contemporary Jewish culture and the exhibition’s focus on generational memory, Kandor 17 seemingly asks us to think about how the Jewish diaspora has been mediated and remediated throughout the past century as we interpret and reinterpret cultural touchstones like Superman. “From Generation to Generation” will be at the Contemporary Jewish Museum until April 2, 2017. [1] Star, Lori. “Director’s Foreword.” From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art. Eds. Pierre-François Galpin and Lily Siegel. San Francisco: The Contemporary Jewish Museum, 2016. 1-3.

[2] Hirsch, Marianne. “Connective Arts of Postmemory.” From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art. Eds. Pierre-François Galpin and Lily Siegel. San Francisco: The Contemporary Jewish Museum, 2016. 69-75. All citations from Hirsch in this post are taken from the exhibition catalogue, although she has defined and refined the concept of postmemory in multiple books and articles, including Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory and The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. [3] This event would become known as one of many “Bloody Sundays,” see Ann Rigney’s earlier blog post, “Transnational Bloody Sundays: Multi-Sited Memory.” [4] The history of which was fictionally represented by Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize winning The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000).

2 Comments

I woke up this morning to news of the death of a good friend, Okla Elliott. I walked around campus much of the day, stunned. For me, nowhere in this town isn’t touched by his memory. (And no one: I suppose I owe him some gratitude for introducing Priscilla and me. We didn’t talk that night beyond hello, but he remained steadfastly convinced that she and I should not only date, but marry, long before we had spent our first real days together). I met Okla my first semester in grad school in 2010, in a class with Nancy M Blake. I found him loud and brash, but by the time the semester closed I was warming to his outgoing brilliance. We bonded over Bushmills and Bad Religion, started getting dinner after class each week. Pretty soon, hardly a day went by without at least an hour’s chat over coffee. We’d spend hours talking and reading at the coffee shop, only to grab dinner, get some Bushmill’s, and head to his place to argue about Heidegger, read poetry at each other, and discuss each and every stupid thing that came into our over-read heads. So many drunken nights of dancing, stomping, and singing. So many times we infuriated each other. So many times we didn’t. All were minor miracles. Okla was, as so many are remembering, a great friend. He was unfailingly encouraging. And he took real interest in the interests of those around him. Of course, he was also a competitive friend, a frustrating friend, even a spiteful friend. But he was, invariably, a friend. And an incredibly vivacious one at that. How many people must be asking themselves now, with me, how a force of nature like that can simply have stopped. By his own accounting (which he offered daily on Facebook), any given day couldn’t get any better, and every taco he made was the kind of genius that gods bow down before. I am grateful to have spent so much time with someone so in love with the world. Over the last couple of years, various frictions grew a polite diffidence between us. I’m not sad about that. We had our years of brilliant friendship. I *am* sad, though, that the world has been deprived of such a machine of creativity, so serious a teacher, and so intense a friend. I was looking forward to catching up with him one of these days, which is now not to be. But there is one thing I could count on: a long night of conversation with Okla would always end with a hug, a handshake, and his saying, “It was a pleasure and honor, as always.” Well, brother, it really was a pleasure and an honor. And I will always remember it. - Matt Nelson I am heartbroken to learn about my friend Okla Elliott's death. Many have spoken more eloquently than me about his work as a poet, a novelist, a literary critic, and a scholar. I will cherish the memories of grabbing bucket-sized iced lattes before going to talks on the Illinois campus, reading for hours in coffee shops together when everyone else left campus for the summer, collaborating on scholarly projects, hitting the gym only to stuff our faces with Thai food right after, and lengthy conversations about philosophy. Dear "robot monkey man", you are dearly missed. - Priscilla Charrat Nelson Okla Jeff Elliott passed unexpectedly in his sleep on March 19, 2017. He will be remembered as a prolific writer, teacher, mentor, beloved brother and friend. He is survived by his mother, Freida Elliott, sisters, Vickie Elliott Brammer and Flora Elliott D'Souza, and nieces and nephew Hannah Brammer, Sabrina D'Souza, and Michael Brammer. Okla earned a PhD in comparative literature from the University of Illinois, an MFA in creative writing from The Ohio State University, and a certificate in legal studies from Purdue University . Okla published widely in national and international literary magazines, journals, and newspapers. He was the author of several works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, including From the Crooked Timber, The Cartographer’s Ink, The Doors You Mark Are Your Own, Blackbirds in September, Bernie Sanders: The Essential Guide, and Pope Francis: The Essential Guide. He was a cofounder and editor of New American Press and MAYDAY Magazine, where he encouraged and cultivated the talent of both new and established writers. He also co-founded a blog for literary and political commentary, As It Ought to Be. Overcoming the obstacles of growing up poor and losing his father at age ten, Okla was an advocate for education as a pathway out of poverty. His too-short life served as a witness to his philosophy. His life and his loss touch his students, colleagues, friends, and family. He will be missed, but he lives on in his words, his genius, and our hearts." - David Bowen I'm so overwhelmed to learn of the death of my friend and former colleague Okla Elliott today. I noticed his photos in my Facebook feed this morning and without even reading the context simply assumed he'd published a new German translation, another poetry anthology or received a glowing interview somewhere about his last novel. It feels disingenuous writing about how intensely news of his death is making me feel right now, crying as I write this, without also explaining that in the early years that I knew him, now more than six years ago, we argued so so often. I don't think there is anyone who has unfriended and refriended me more on Facebook over the years than Okla. Maybe precisely because we shared so many of the same very specific interests (from Sartre to the legacy of Stalin in Marxism) we butted heads on nearly every issue. In an atmosphere of quiet consensus I was drawn to Okla as a strong, confident interlocutor who wouldn't back down from an argument, someone who believed in the inherent value of debate, someone who resisted political chauvinism for the sake of keeping open a space for critical thought. Even after we stopped talking, I thought I'd have the chance someday to catch up over a drink and remark on the irony that so many years after our first and most heated arguments about theology, our positions had seemingly reversed. I came to define and redefine my intellectual positions against him. I really always felt he would be there in the background, his constant overachieving compelling me to work harder. I always imagined telling him someday how much I respect him and what an enormously positive effect on my intellectual development he had. I'm absolutely devastated to learn of his death today. - Brandon Carr Okla was so alive in the world that it does not seem possible he is not here...his formidable energy seemed like it would never end. When he was working on his dissertation Okla would come to my office often; without fail he arrived carrying a huge iced coffee, no matter what the season. But the potential energy in an enormous coffee was nothing compared to Okla’s own vibrant mind. We would talk about all of his many ideas and I always felt that my role was, rather than offering any new ideas, to trim those thoughts lest they stray into too many directions. After Okla defended his dissertation I was so proud that he took up a post as an Assistant Professor at Misericordia. We were in touch often over email and Facebook and I was delighted that he undertook the important project of building a Holocaust pedagogy website. When prospective graduate students visit Illinois I always hold up Okla as a model. His voracious mind could take in Bernie Sanders and Pope Francis all while writing fiction and poetry and teaching. He was (why must I use the past tense?) an energetic person but someone whose traumatic past haunted him. More than once I cried reading his fictionalized autobiographical stories. His prose was often sparse but very powerful and I don’t think he would ever have run out of beautiful words with which to express his many and variegated thoughts. Already on facebook people who knew him in person and also a surprising number who knew him only virtually have been describing Okla as a generous friend and colleague who always supported and encouraged them, who often argued with them, and who was always onto some new thought. He was indeed extremely generous and consistently went out of his way to help publish and broadcast other people’s thoughts and ideas. He was a tireless advocate for small presses and independent publishing. I was very fond of him, and very proud of him, and he should have been able to continue to be the force of nature that he was. - Brett Kaplan Feeling totally shocked this morning, having learned of the sudden death of my former classmate and friend Okla Elliott. A creative writer and scholar of comparative literature, law, and (most recently) religion, Okla always seemed to be guided by a boundless energy and enthusiasm for learning that I found astonishing. He continued taking seminars while dissertating (and teaching) out of love for the experience, and always seemed to be working on multiple involved projects concurrently. In recent years, his prolific social media posts offered windows into his latest labors of love. Really struggling to process this one. - Valerie O’Brien Many people will have seen this by now, but my good friend, longtime roommate, and literary collaborator Okla Elliott passed away in his sleep on March 19th. He was a brilliant mind and someone who was incredibly generous with me and changed my life for the better. I apologize to anyone close to him who is finding this out through Facebook. We wanted to contact you all by phone first, but his personal and professional spheres were large and it just wasn't possible before the news came out in other ways. That is all I want to write for now. David Bowen has posted a nice obituary on Okla's timeline for those wishing to read it. - Raul Clement My Dearest Okla Elliott, Not long were my days in Illinois before I met you, standing there amidst the rest of the comparative literature students and faculty, beaming with happiness and that beard covered smile I came to love so much, and ever since I was always incredibly grateful for the interest you showed in me and my work, your guidance and helping hand, and your willingness to take on a reclusive and introverted Swede. The two years I spent in Illinois, with you in my life, will forever stand out among the greatest in my life. Okla, you took me in, and not only as a roommate, but as an equal, as a fellow student, as a colleague, and as a debater of many things literary, and even though I could never convince you of the brilliance of my genre classification, you still stood there as civil as ever and told me your argument. This is one of the many things I will miss now that you are gone, your undying love to do and fight for what is right, your incredible fortitude to take the good fight, and perhaps most of all, to always be civil when others argued against you. You always took the fights, when I never could. My dearest Okla, I will forever cherish our moments together, and I always wish I were there with you more, in your many and long conversations with Raul and Matt, but we did have many fantastic dinners and lunches together, not the least of which were your absolutely amazing tacos. You were always there for me. I will forever miss you, my dear friend, my roommate, my brother. - Fredrik Wittsten Heartbroken to hear that we have lost Okla Elliott, an amazing writer and person. It was an honor and pleasure to co-edit New Poetry from the Midwest alongside him. He was a seemingly tireless creator and advocate for other writers. I was consistently inspired by his generosity of spirit and energy--he was such a force of empathy and good in the literary community. He made an impact on so many people--I know there are many grieving for him, and to all of you, I send hugs and compassion. - Hannah Stephenson I am absolutely devastated to learn that Okla Elliott has passed away. The co-founder and managing editor of As It Ought To Be, he was my editor for 10 years. I feel like that sentence is too smal to contain all that it means, so I will just say it again: He was my editor for 10 years. He changed my life in so many ways, all of them for the better. I don't envy the person charged with writing Okla's eulogy; every time I start to write about who Okla was and all he accomplished I am humbled by the sheer weight of the task. Never have I known a man more prolific, more passionate, more capable. He was the smartest and most well-read person I knew, period. And he was the very definition of a mensch. I am thinking in this moment of grief of all of the people I know because of Okla, of the many friends we had in common and the many people who are in my life because of this man, people whose lives, like mine, were touched beyond words by this incomparable human: Raul Clement, Yahya T. Ali, John Guzlowski, Chandra EA Dickson, Karen Craigo, Chase Dimock, Matt Gonzalez, Deborah Dubroff, and many others who I am forgetting in this moment in my grief. If you go to Okla's memorial page here on Facebook you'll see post after post extolling his virtues and attempting to remember his innumerable accomplishments. I want to add one thing here that I think important. For most of the 10 years I knew him, Okla was an ardent atheist. This past summer he nearly died twice, but survived, and in his surviving he found god. I am not a traditional believer myself, but I was moved by Okla's newfound relationship with god, and with the countless ways Okla lived a life in the spirit of the core values of his religion: kindness to others, care for the downtrodden, generosity, social welfare, and an abundance of love. Looking back, I can't help but wonder if there were not some divine purpose in sparing his life twice this past year and only taking him from this earth once he had reconnected with his god. At the very least, I know his transformation brought him comfort. But I hope it's more than that. I hope he knew something that many of us don't. I hope he was right, and that he is now in a place worthy of a man who lived his life in righteousness, as Okla did. My heart goes out to everyone who is grieving for this loss. The world will never know another like you. You will be missed more than we can imagine. - Tristan Chaika ENTRANCES AND EXITS by Okla Elliott When I was a younger man, a boy, the intrigue of washing machine doors trunks, windows, manholes--secret passages of all sorts--possessed me. I spent hours passing through and back through a simple hole in the wall of a condemned house careful to step with the other foot or at a new angle each time, conducting experiments that might foretell how the world would receive me and how I would leave. A day later, and I still can't process the fact that Okla Elliott, 39 years old, is gone. That someone so full of life could be taken from life, and so young, is incomprehensible. It makes me feel vulnerable and very, very small. Which I am; which we all are. It just sucks to be reminded of it.

I only knew him on the internet - one of his scores of fans aka "amigos internetos" as he called his online friends - but from what I can tell he is the most influential, impactful non-famous person I've ever known. The outpouring of grief I've seen on his Facebook page is beyond anything I've ever seen for anyone, and that includes famous people. It was thrilling to watch his career - as a poet, novelist, professor, translator, editor, and news commentator - unravel in ever more dazzling twists and turns. He made you believe in his potential, and then showed you time and again that your faith was not misplaced; indeed, that you had somehow managed to both believe in him and underestimate him at the same time. And along the way, he supported so many people in their own journeys. I don't know how he found time for it all, but someone he did it. He had an impressive work ethic. Most of all, I admired his courageous intellectual honesty. By now, I think we were all getting on the same page. Okla was going to be a huge force of good in the world, and we were on the edge of our seats; couldn't wait to see what he was going to do next. Except that his life was cut short before "next" could happen. It's a staggering loss. My condolences go out to his friends, family, colleagues and students. He was so open about his life, and he made us care about you through his stories of you, and we care about you now in your time of grief. - Eliana Mariella The sixth Mnemonics: Network for Memory Studies summer school will be hosted by the Frankfurt Memory Studies Platform from September 7-9, 2017 at Goethe University Frankfurt. Confirmed keynote speakers are Aleida Assmann (University of Konstanz), Andreas Huyssen (Columbia University, New York) and Anna Reading (King’s College, London). This year’s Mnemonics summer school addresses the ‘social life of memory’. Memory studies is based on the premise that memories emerge (as Maurice Halbwachs argued) within ‘social frameworks’. But this is just the first stage of memory’s social dynamics. Those memories which have an impact in culture don’t just stand still, but lead a vibrant ‘social life’: They are mediated and remediated, emphatically welcomed and harshly criticized, handed on across generations, they travel across space, become connected with other memories or turn into a paradigm for further experience. Conversely, books about the past that are not sold and read, oral stories that are not passed on to grandchildren, history films that are not screened and reviewed, monuments that nobody visits, public apologies that do not engender heated debates – all these will fail to have an effect in memory culture. Memory ‘lives’ only insofar as it is continually shared among people, moves from minds and bodies to media and back again, is performed, remediated, translated, received, discussed and negotiated. Once we conceive of objects and media as part of memory culture, we realize that these are not stable entities, containing unalterable meanings, but that they unfold their mnemonic significance only within dynamic and transitory social processes. This insight entails methodological consequences. It creates the need to use more complex theory/methodology-designs in order to do justice to the moving constellations we study. This may also mean connecting humanities- and social sciences-approaches. Reception theories, reader response theories, audience studies, performance studies, sociological and political science-methods, museum visitor studies, social history, social psychology, ethnography, or actor-network theory – these all belong to the long list of approaches that we may want to draw on in order to study what our research group here in Frankfurt calls ‘socio-medial constellations’ of memory. The metaphor of the ‘social life of memory’ is not yet a clear-cut concept. However, it resonates with existing ideas, from Mikhail Bakhtin’s ‘social life of discourse’ to Arjun Appadurai’s ‘social life of things’ or Alondra Nelson’s ‘the social life of DNA’. It also brings to mind the ‘afterlife’ of artworks as it was addressed by Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin. More recently, and within the new memory studies, Astrid Erll and Stephanie Wodianka have addressed the life of ‘memory-making films’ by studying their embeddedness in social contexts and in ‘plurimedial constellations’. In her study of Walter Scott, Ann Rigney has theorized the social (after-)lives of texts and authors in cultural memory. The summer school welcomes paper proposals that display a keen interest in the dynamic interplay of medial and social aspects of memory culture and that suggest ways to explore ‘the social life of memory’ – from the perspectives of contemporary memory cultures across the globe as well as from historical viewpoints. Possible topics include, but are emphatically not restricted to, the following:

Confirmed Keynote Speakers: Aleida Assmann is Professor emeritus in English Literature at the University of Konstanz. She has been Visiting Professor at Princeton (2001), Yale (2002, 2003 and 2005) as well as other universities and has received numerous prizes. Among her recent publications in the field of memory studies are Formen des Vergessens (Wallstein, 2016), Shadows of Trauma: Memory and the Politics of Postwar Identity (Fordham University Press, 2015) and Das neue Unbehagen an der Erinnerungskultur: Eine Intervention (C. H. Beck, 2013). An important earlier contribution to the field of memory studies, Erinnerungsräume: Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses (C. H. Beck, 1999), has also been translated into English, as Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge University Press, 2011). Andreas Huyssen is the Villard Professor of German and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, New York. Before joining Columbia, he taught at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee from 1971 until 1986. He served as founding director of the Center for Comparative Literature and Society (1998-2003). He is one of the founding editors of New German Critique and is on the editorial board of various journals. Among his publications in the field of memory studies are William Kentridge, Nalini Malani: The Shadow Play as Medium of Memory (Charta, 2013), Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory (Stanford University Press, 2003) and Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (Routledge, 1995). Anna Reading is Professor of Culture and Creative Industries at King’s College London. She is also a journalist and playwright. Before joining King’s College, she was a researcher at the University of Westminster (1992-1995) and a Lecturer in the Department of English Literature at the University of Lodz (1988-1989). She directed the Centre for Media and Culture Research, which she founded, at London South Bank University from 2009 to 2011 and was a member of the Institute of Culture and Society at the University of Western Sydney from 2010 to 2012. Among her recent publications in the field of memory studies are Gender and Memory in the Digital Age (Palgrave, 2016), her co-edited volume Save as… Digital Memories (Palgrave, 2009) with Joanne Garde-Hansen and Andrew Hoskins, and The Social Inheritance of the Holocaust: Gender, Culture and Memory (Palgrave, 2002). Format: The Mnemonics summer school serves as an interactive forum in which junior and senior memory scholars meet in an informal and convivial setting to discuss each other’s work and to reflect on new developments in the field of memory studies. The objective is to help graduate students refine their research questions, strengthen the methodological and theoretical underpinnings of their projects, and gain further insight into current trends in memory scholarship. Each of the three days of the summer school will start with a keynote lecture, followed by sessions consisting of three graduate student papers, responses and extensive Q&A. Participants are expected to be in attendance for the full three days of the summer school. In order to foster incisive and targeted feedback, all accepted papers will be pre-circulated among the participants and each presentation session will be chaired by a senior scholar who will also act as respondent. Practical Information: Local organizers: Mnemonics 2017 will be hosted by the Frankfurt Memory Studies Platform, which is an initiative of the Frankfurt Humanities Research Centre. Both are located at Goethe University Frankfurt. Organizers are Astrid Erll, professor at the Institute for England and America Studies at Goethe University, Erin Högerle and Jarula M. I. Wegner, PhD candidates on the DFG research project “Migration and Transcultural Memory: Literature, Film the ‘Social Life’ of Memory Media”. Where: Campus Westend of Goethe University Frankfurt, located in Frankfurt Westend and easily accessible by car, train (Frankfurt central station) or airplane (Frankfurt Airport, FRA). When: September 7-9, 2017 Costs: 200€. The fee includes conference registration, a private bedroom at Ibis Hotel Centrum close to Frankfurt central station for three nights (September 6-9) and most meals. Travel to Goethe University is not covered, and prospective attendees are encouraged to check travel costs in advance. Scholarship: Memory studies is an increasingly global field, and we hope to see this reflected in the composition of the participant group. We therefore encourage graduate students based at non-European institutions, particularly in the Global South, to apply for admission to the summer school. In order to facilitate their participation, Frankfurt offers one scholarship for a fully-funded place at the summer school. Awarded on the basis of both merit and need, it covers all travel expenses, hotel costs, a daily allowance, the conference fee and visa assistance. If you want to be considered for this scholarship, please indicate this in your application, include a budget estimate and disclose any other sources of funding. Submission: Submissions are open to all graduate students interested in memory studies. About half of the 24 available places are reserved for students affiliated with Mnemonics partner institutions. Send: A 300-word abstract for a 15-minute paper (including title, presenter’s name and institutional affiliation), a description of your graduate research project (one paragraph) and a short CV (max. one page) as a single Word or PDF document to: [email protected] Deadline: March 31, 2017 Notification of acceptance: May 15, 2017 Deadline for submission of paper drafts: August 15, 2017 Questions? Write to [email protected] Mnemonics homepage: http://www.mnemonics.ugent.be/ Mnemonics on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/groups/mnemonics.network/ Mnemonics on Twitter: @mnemonics_net Frankfurt Memory Studies Platform homepage: http://www.memorystudies-frankfurt.com/ Frankfurt Humanities Research Centre homepage: http://fzhg.org/ References

Appadurai, Arjun. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1986. Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator: An Introduction to the Translation of Baudelaire’s Tableaux parisiens.” 1923. Reprint. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968. 69-82. Erll, Astrid and Stephanie Wodianka, eds. Film und kulturelle Erinnerung. Plurimediale Konstellationen. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2008. Nelson, Alondra. The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation after the Genome. Boston: Beacon Press, 2016. Rigney, Ann. The Afterlives of Walter Scot: Memory on The Move. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Warburg, Aby. The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: Contributions to the Cultural History of the European Renaissance. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 1999. |

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed