A ForumThis Days and Memory forum brings together four scholars of cultural memory, based on three continents, who have been actively involved in promoting the transnational turn in memory studies: Rosanne Kennedy (Australian National University), Ann Rigney (Utrecht University), Michael Rothberg (University of Illinois), and Debarati Sanyal (University of California, Berkeley). Three of the presenters (Kennedy, Rigney, and Rothberg) are part of an internationally funded research project called the Network in Transnational Memory Studies (NITMES), which was initiated by Ann Rigney with support from the NWO (The Dutch Research Council). Through a series of conferences, faculty exchanges, and publications—including this one—NITMES seeks to provide a platform for new debates in cultural memory studies.

In the past 25 years, memory studies has emerged as a new interdisciplinary field of cultural inquiry. It aims for insight into practices of public remembrance and the sociocultural dynamics through which mediations of the past shape collective identities and inform social action. The development of this field was linked from the outset to investigations of national memory cultures and institutions, with the nation‐state taken as the most self‐evident framework for analysis. Pierre Nora’s pioneering, influential, and contested study Les Lieux de Memoire (1984‐1992) encapsulated the link between “territorialization” (focusing on how memory narratives are fixed, located, contained, “inherited”) and the nation (as the self‐evident frame within which narratives operate and identities are shaped). With the turn towards transnational approaches in the last decade, however, Nora's concept of “sites of memory” has come under pressure as the assumed framework for memory studies. In our increasingly globalized, networked, and mediated world, alternatives to national models of memory as a resource for identity constructions are beginning to emerge without yet being fully understood. This forum explores the consequences of the transnational turn for the study of sites, practices, and noeuds or knots of memory. The short papers collected here—originally presented at the Modern Language Association Convention in Vancouver in January 2015 on a roundtable organized by Rosanne Kennedy and Michael Rothberg—track the intersection of memory and politics across a range of sites: from Ireland to Indonesia, from Germany to Kurdistan, and beyond. At stake in these discussions are such multivalenced categories as complicity, human rights, and internationalism, which play out in relation to what Astrid Erll has called "traveling memories." Paying close attention to a range of media—from photographs and films to literary texts and monuments—contributors interrogate the mobilizing potential of public remembrance, its catalyzing force in activist projects both within and beyond nation-states. You can find the papers here: 1. Debarati Sanyal, “Memory in Complicity” 2. Rosanne Kennedy, “The Act of Killing, the Global Memory Imperative, and Trans/national Accountability” 3. Michael Rothberg, “Remembering Ronahî, Remembering Internationalism” 4. Ann Rigney, “Transnational Bloody Sundays: Multi-Sited Memory” We invite you to join the discussion!

1 Comment

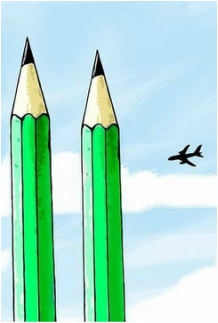

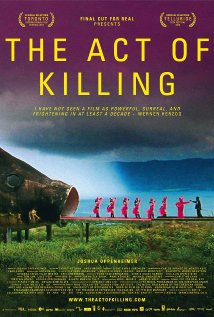

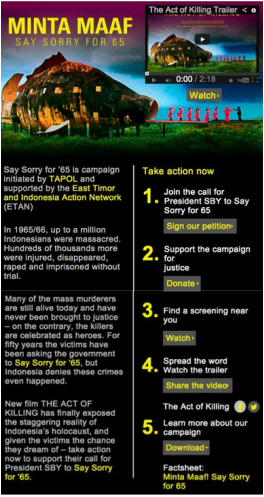

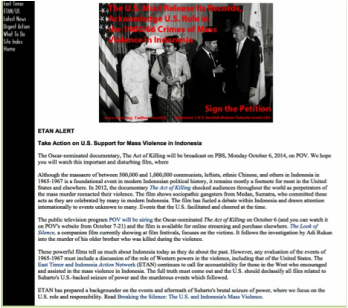

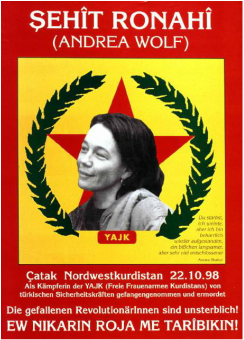

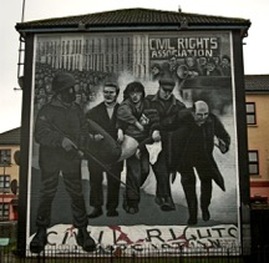

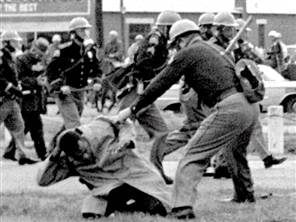

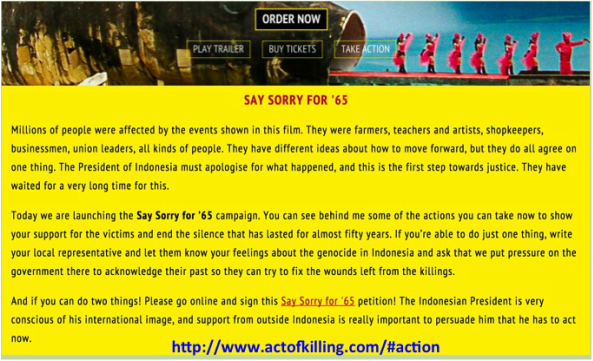

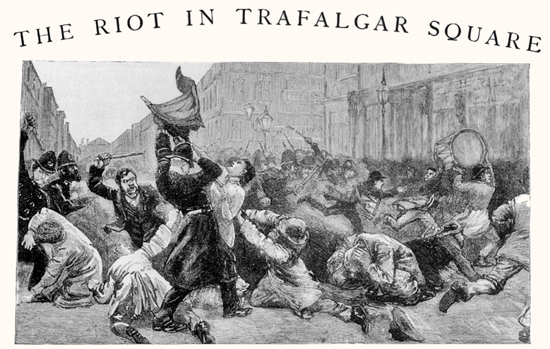

This post is part one of a four-part forum: "Transnational Memories: Sites, Knots, Methods." An earlier version was presented as part of a roundtable at the Modern Language Association's 2015 Convention in Vancouver that featured Rosanne Kennedy, Ann Rigney, Michael Rothberg, and Debarati Sanyal.  The imperative to remember foundational violence such as the Holocaust, slavery, apartheid, partition, or colonialism has often led the study of memory to compartmentalize these events as singular ethno-cultural or national traumas. Yet in the past two decades, we've seen a shift from memory contained to memory unbound. Spatial models of remembrance such as Pierre Nora's lieux de memoire, or “sites of memory,” and the containment that they can presume, have been yielding to figures of process and motion. Richard Crownshaw describes this as a shift from centripetal models of memory, where group or national identity coalesces around collective memories of events, to a centrifugal movement that releases cultural memory from ethnic, territorial, and national particularisms into transnational flows and cosmopolitan contents.[1] Today, memory is on the move, and national histories are being rethought through models of motion, entanglement, crossings and linkage in order to capture the fluid practices of remembrance in a postcolonial age of globalization, mass migration, and technological connection. These include the compelling models developed by my co-panelists: Rosanne Kenney's moving testimony, Ann Rigney's transnational memory, and Michael Rothberg's multidirectional memory.[2] In the few minutes that I have today, I'd like to sketch out how complicity can be a useful term as we consider memory's movement across national and ethno-cultural borders.[3]  Charlie Hebdo, "The French 9/11" Charlie Hebdo, "The French 9/11" In a time of unprecedented connection with other peoples and histories, complicity and solidarity may be two sides of the same coin. Today, the recognition of marginalized histories of violence and loss remains an urgent task. But this is not to say that an additive model of recognition and remembrance is enough, or that memory's movement is inherently progressive or inclusive. If this movement can shake up traditions of remembrance, allowing new identities and affiliations to emerge, its pathways can also lead to dangerous intersections, where identification leads to appropriation, where political uses of memory collide with the ethical obligations of testimony, where difference is eclipsed into sameness, or where particular pasts are absorbed under one paradigm of historical trauma. We see a particularly dangerous intersection in the transnational movement of memory in France right now, where the shootings at Charlie Hebdo and an Hyper Cacher are referred to as "the French 9/11" and analogized to Nazi Germany's Kristallnacht... All this to say that even as we look at memory's movement across nations, histories and identities, we must also look out for the range of causes that this movement serves, the solidarities that are opened but also those that are foreclosed. If, as Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider have observed, "the container of the nation state is in the process of slowly being cracked," memory still moves within the political constraints of an often national or identitarian field whose channels are limited by competing political interests and ideological investments. [4] Complicity, I want to suggest, helps us track the complexity of memory's movement across national borders and ethno-cultural difference. Now, complicity usually means participation in wrongdoing, or collaboration with evil. But its Latin root, complicare, 'to fold together' reminds us of its secondary and now archaic usage, which is 'the state of being complex or involved'. In French, the word complicité also means understanding and intimacy. Complicity as a term can help us think about the folding together or gathering of subject positions, histories and memories, that characterizes the emerging methods of transnational, transcultural memory studies. The recognition of complicity—of the folds that bring different histories into contact, but also of the places we occupy in a historical fold— requires us to consider our contradictory position within the political fabric of a given moment, as victims, perpetrators, accomplices, witnesses, bystanders, consumers or spectators, and more often than not, an uneasy combination of the above (as Rosanne Kennedy suggests on this panel, in the context of the "Say Sorry for '65" campaign). Since the 1990's, memory studies in conjunction with trauma theory has tended to address historical violence, from the Holocaust to 9/11, primarily through the perspective of the victim. Yet more recently we've witnessed a turn towards complicity and perpetration, a turn that might well be a return, since in the aftermath of World War Two, at least in the French-speaking context, complicity was a key vector of transnational memory (e.g. the folding together of Nazi atrocity and French colonial violence). On the contemporary international cultural scene, examples of this renewed turn to testimony's "darker side" include Bernhard Schlink's The Reader, Rithy Panh's documentary on the Khmer Rouge, S21, Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing, or Jonathan Littell's Les Bienveillantes, to which I'll return. This potential reorientation of cultural imaginaries towards complicity and perpetration rather than trauma and victimhood is valuable provided it doesn't congeal into facile pronouncements on– and handwringing about– our structural complicity with global violence. An animating, rather than paralyzing, awareness of complicity can alert us to what legal scholar Christopher Kutz calls "our mediated relationship to harms."[5] It can lead to a better understanding of the past's reverberations in the present, a clearer grasp of the many forces that mediate our agency. Complicity, as I understand it, is not a fixed stance but a structure of commitment that provides an alternative to affect-based discourses of trauma, melancholy or shame, and opens up a robust, yet self-reflexive, engagement with the violence of history.  I only have time for one literary example here: Franco-American author Jonathan Littell's monumental Les Bienveillantes, translated as The Kindly Ones. Published in 2006, this bestseller unleashed polemics in France and beyond due to its transgression of several taboos on Holocaust representation. I will simply evoke its transgressive treatment of identification. Holocaust testimony is usually understood to be the account of a survivor and victim; its reception is theorized through models of intimacy and identification. Readers or viewers are invited to become secondary witnesses and hosts to the representation of a victim’s trauma. The Kindly Ones, however, is a first-person narrative that coerces us into complicity with its Nazi protagonist for over 900 pages, even if this identification with the perpetrator is constantly sabotaged by the text's irony. Thus, we are asked to sustain the tension between intimacy and irony, identification and distance, as we witness the atrocities of the Third Reich in their visceral horror and bureaucratic abstraction. To readers who inhabit a potentially reified culture of Holocaust memory, this alternation between complicity and irony forces us to reimagine Nazism in relation to ourselves, without abdicating to facile claims about the banality of evil or that "we are all perpetrators." The Kindly Ones is also a historical investigation of transnational atrocity. It explores the colonial archive of Nazism's Eastward expansion, reminding us that for Hitler the Russian space was analogous to British India. In doing so, it highlights the conceptual and strategic complicities between the Final Solution, other Nazi programs of extermination, and the massacres and genocides of Western imperialism including American settler genocide, the US in Vietnam and France in Algeria. The novel aims to create a sounding board ("une caisse de résonance," as Littell puts it) between these distinctive legacies of racialized violence while gesturing towards the contemporary horizon.[6] Its author is also a journalist who has written about current sites of conflict such as Syria and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The interplay of complicity and irony in The Kindly Ones, its cognitive, affective, and ultimately ethical demands on readers, reminds us that if fiction can experiment with historical archives and practices of remembrance, the responsibility to animate these virtual memories lies in their reception. Reading is where an ethics of memory in motion can develop. To conclude, last year at an MLA presidential panel on vulnerability, Andreas Huyssen asked us to think about the relationship between memory discourses and human rights in order to energize present and future-oriented struggles. It seems to me that complicity has a role to play in this as well. An attunement to one's complicity with both catastrophic and slow forms of violence that one might seek to prevent, challenge or repair would nuance the universalism of humanitarian discourses and help to identify the constraints under which certain subjects are produced as objects of intervention, compassion and assistance. Here too complicity and solidarity may be two sides of the same coin. [1] Richard Crownshaw, Introduction to the special issue on transcultural memory, Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011):1. [2] Rosanne Kennedy, "Moving Testimony: Human Rights, Palestinian Memory, and the Transnational Public Sphere," in Chiara de Cesari and Ann Rigney (ed.), Transnational Memory Circulation, Articulation, and Scales (Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, October 2014); Ann Rigney, Introduction to Transnational Memory Circulation, Articulation, and Scales (Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2014); Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2009). [3] For an expanded version of this argument, see Debarati Sanyal, Memory and Complicity: Migrations of Holocaust Remembrance (New York: Fordham University Press, 2015). [4] Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 195 [5] Christopher Kutz, Complicity: Ethics and Law for a Collective Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 2. [6] Jonathan Littell and Pierre Nora, “Conversation sur l’histoire et le roman,” in Le débat 144 (March/April 2007): 43–44. Other Posts in this ForumThis post is part two of a four-part forum: "Transnational Memories: Sites, Knots, Methods." An earlier version was presented as part of a roundtable at the Modern Language Association's 2015 Convention in Vancouver that featured Rosanne Kennedy, Ann Rigney, Michael Rothberg, and Debarati Sanyal.  In 2012, Joshua Oppenheimer’s celebrated film, The Act of Killing, was released to significant acclaim, garnering awards at film festivals around the world.[1] The film remembers the massacre of 500,000 alleged communists in Indonesia in 1965-66. In interviews, Oppenheimer states that he hoped to open a national conversation in Indonesia on the killings, abetted and protected by the military under the leadership of General Suharto. During Suharto’s reign (1966-1998), the killings were not so much ‘forgotten’ but deliberately misremembered: a four and a half hour propaganda film -- mandatory viewing for all school students -- narrated the slaughter as a patriotic act of ridding the nation of the ‘evil’ of communism.[2] The Act of Killing aims to bring into visibility the culture of impunity that still persists in Indonesia, and enables perpetrators, who have never faced justice, to live as ‘free men’. Over a five-year period, Oppenheimer and his anonymous Indonesian co-director filmed one of the executioners, Anwar Congo, and his circle of friends as they discussed and re-enacted their acts of killing through a range of Hollywood genres. In focusing the camera exclusively on Indonesian perpetrators and locations, The Act of Killing represents the genocide through a national frame. My focus here is not on the film, fascinating though it is, but rather on its human rights packaging. The film has been embedded in campaigns for justice on behalf of the victims, tying publicity for the film with advocacy for human rights. Leaving aside the moot question of the efficacy of such campaigns, their websites provide insight into how the film is packaged for travel, to promote the film and address transnational audiences. Of particular relevance for transnational memory studies, these human rights campaigns productively illustrate the workings of the global memory imperative. As elaborated by Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider, the ‘global memory imperative’ refers to the idea that “memories of the Holocaust …have the potential to become the cultural foundation for global human rights politics.”[3] In interviews, Oppenheimer repeatedly invokes Holocaust memory to justify making the film and thereby ‘breaking the silence’ surrounding the mass violence in Indonesia. For instance, he contends that Medan, the town in which Anwar lives, is like Nazi Germany “forty years after the Holocaust” with “the Nazis still in power…” He acknowledges Claude Lanzmann’s Holocaust film, Shoah, and particularly his testimonial methods, as a major influence on his approach to filming The Act of Killing. Of particular significance for my analysis, Levy and Sznaider argue that the global memory imperative is “transforming nation-state sovereignty by subjecting it to international scrutiny,” and by empowering the human rights regime to intervene into current sites of violation.[4] On this conception, the moral imperative to remember the victims of mass violence, activated through the film-human rights campaign assemblage, functions as a spur to global civil society to pressure a nation-state that refuses to acknowledge accountability for violating the rights of victims. How then do these advocacy campaigns use the film’s act of memory to solicit and address their intended publics? How do concepts of the national and transnational play out in these campaigns? ‘Say Sorry for ’65’: Art, Advocacy and Transnational Accountability  Say Sorry for ’65 Campaign Say Sorry for ’65 Campaign The official website for The Act of Killing includes a ‘Take Action’ hyperlink to a bright yellow page titled ‘Say Sorry for ‘65’.[5] The ‘Minta Maaf: Say Sorry for ‘65’ campaign was launched in London on June 28, 2013 by the British human rights organization, TAPOL, which campaigns for human rights in Indonesia, especially in East Timor, West Papua and Aech.[6] (TAPOL means ‘political prisoner’; the organization was formed in 1973 by Carmen Budjiardjo, who was a political prisoner in Indonesia following the massacres.) The campaign is supported by another human rights organization, East Timor Action Network (ETAN), which describes itself as ‘a U.S.-based grassroots organization working in solidarity with the peoples of Timor-Leste (East Timor), West Papua and Indonesia’.[7] The publicity for the ‘Say Sorry’ campaign on The Act of Killing website asks visitors, if they can do one thing, to “write to your local representative and let them know your feelings about the genocide in Indonesia and ask that we put pressure on the government there to acknowledge their past so they can try to fix the wounds left from the killings.”[8] Through this humanitarian appeal, the ‘Say Sorry for ’65’ campaign aims to generate support from global civil society to pressure a national government – Indonesia - for its failure to prosecute the perpetrators and thereby secure justice for the victims. With its familiar rhetoric of ‘feelings’ and ‘wounds’, this campaign positions non-Indonesian signatories as humanitarian subjects, who can express empathy and transnational solidarity with activists working for justice in Indonesia by signing an online petition. The ‘Say Sorry for ‘65’ campaign is an example of deterritorialized advocacy: the ‘you’ that is addressed could be in any geo-political location, as could the ‘local representative’. By contrast, the target is territorialized: the invitation to ‘put pressure on the government there to acknowledge their past’ locates the violence and the responsibility in Indonesia. The ‘Say Sorry’ publicity on the film website asks viewers: “if you can do two things, please ... sign the Say Sorry for 65 Petition: The Indonesian president [at the time, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono] is very conscious of his international image, and support from outside of Indonesia is really important to persuade him that he has to act now.”[9] In this instance, we see the global memory imperative at work: film viewers are addressed as members of a transnational ‘witnessing public’ who can do something to right the wrongs in Indonesia.[10] The ‘Say Sorry’ campaign grounds transnational solidarity in humanitarian values of compassion, justice, witnessing and empathy, but it does not require viewers to consider their own positioning or implication.  ETAN: Acknowledge US Support for Killings ETAN: Acknowledge US Support for Killings Although ETAN, a US-based grassroots human rights organization, supports the ‘Say Sorry for ‘65’ campaign, it has launched a linked campaign to demand that the United States government acknowledge its role in the mass killings in Indonesia in 1965.[11] It invites visitors to watch The Act of Killing on PBS, the American Public Broadcasting Station, and to “take action on US support for mass violence in Indonesia.” It includes fact-sheets detailing the role of the United States in the killings, and a link to Brad Simpson’s article, ‘It’s Our Act of Killing Too,’ published in The Nation.[12] By including these ‘factsheets’ and links, the ETAN campaign acts as a prosthetic to the film, extending its act of memory beyond the nation. It thereby addresses one of the criticisms of The Act of Killing – that is fails to reveal the extensive involvement of the United States and other Western nations in the massacres.  ETAN: Acknowledge US Support for Killings ETAN: Acknowledge US Support for Killings The rhetorical address of the ETAN campaign for US accountability differs markedly from the ‘Say Sorry for 65’ campaign. The ‘Say Sorry’ campaign directs international scrutiny in one direction only – ‘over there’ – and solicits global civil society to pressure the Indonesian government to apologize. While supporting the ‘Say Sorry’ campaign’s call for justice for victims in Indonesia, ETAN’s campaign for US accountability directs attention to the American home front and thereby reterritorializes accountability for the genocide. It addresses Americans as participants in a national public sphere, and – to borrow a term from Michael Rothberg -- as ‘implicated subjects’ in this past.[13] The campaign solicits Americans to pressure their own government to acknowledge its complicity in the massacre by, for instance, signing a petition asking the United States government to “declassify and release all documents related to the U.S. role in the 1965/66 mass violence, including the CIA's so-called "job files."[14] As these two campaigns illustrate, human rights discourse and organizations provide a transit lane that facilitates the global travels of The Act of Killing. But these border-crossing campaigns have different effects: the ‘Say Sorry’ campaign, while soliciting a transnational humanitarian public to pressure Indonesia, nonetheless reinforces nationalism by locating responsibility for the mass killings within Indonesia alone. By contrast, the ‘Acknowledge US Support’ campaign uses the film’s memory of genocide to demand accountability from the US, thereby transnationalizing accountability. World Memory and the Transnational Public SphereWhat issues does this case raise for transnational memory studies? To the extent that The Act of Killing aims not simply to remember the killings, but to facilitate a dialogue, in the present, about the genocide and justice for survivors and victims’ families, it brings into play the issue of the public sphere, for it is in the public sphere that advocacy does its work. As Nancy Fraser (2007) has argued, the concept of the public sphere has implicitly assumed a Westphalian frame, in which the public sphere was “a bounded political community with its own territorial state”, which authorized citizens to hold their national governments accountable.[15] In memory studies today it is widely acknowledged that ‘sites of memory’ are no longer contained by the nation-state, and that memory texts and practices circulate across national borders. The transnational travels of memory render the issue of the public sphere – and of how memory texts are addressed to transnational publics (who are also simultaneously ‘national’) -- a compelling one for memory scholars.[16] As we have seen in relation to the human rights campaigns that aid the transnational circulation of The Act of Killing, global civil society – rather than a national public sphere - is called upon to police nation-states of which its members are not citizens. This is, of course, a significant development facilitated by the growth of a powerful global human rights regime. But as the ETAN case shows, citizens can also exercise transnational solidarity – and perhaps with more integrity and self-reflexivity – with victims and survivors elsewhere by acting as members of a national public sphere, to hold our own governments to accountability for their actions, and simultaneously recognize our own implication in these events. [1] The film is directed by Joshua Oppenheimer and an anonymous Indonesian co-director; see http://www.actofkilling.com. Accessed 4 March 2015. [2] Scenes from this film are featured in the Director’s Cut of The Act of Killing. [3] Levy, Daniel and Natan Sznaider, The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age. Trans. Assenka Oksiloff. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2006: 4. [4] Levy, Daniel, and Natan Sznaider. Human Rights and Memory. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2010: 149. [5] See the ‘Take Action’ link on the film’s website: http://www.actofkilling.com/#action. Accessed 4 March 2015. [6] http://www.tapol.org/press-statements/say-sorry-‘65-campaign-launches-tapol’s-40th-anniversary [7] http://www.etan.org/action/saysorry.htm. Accessed 4 March 2015. [8] See the ‘Say Sorry for 65’ campaign publicity on The Act of Killing website: http://www.actofkilling.com/#action. This page has a hyperlink to an online petition, hosted by ‘change.org’ (https://www.change.org/p/president-sby-say-sorry-for-65). Accessed 4 March 2015 [9] http://www.actofkilling.com/#action. Accessed 4 March 2015. [10] On the concept of a ‘witnessing public’ see Meg McLagan, “Principles, Publicity, and Politics: Notes on Human Rights Media.” American Anthropologist 105.3 (2003): 609–612. [11] http://www.etan.org/news/2014/09breaking_the_silence.htm. Accessed 4 March 2015. [12] Originally published in The Nation, Feb. 28, 2014; see: http://www.thenation.com/article/178592/its-our-act-killing-too. Accessed 4 March 2015. [13] Rothberg, Michael. “Beyond Tancred and Clorinda: Trauma Theory for Implicated Subjects.” The Future of Trauma Theory. Eds. Gert Buelens, Sam Durrant, and Robert Eaglestone.London: Routledge, 2013. xi–xviii. [14] http://www.etan.org/action/14taokpbs.htm [15] Fraser, Nancy. “Transnationalizing the Public Sphere: On the Legitimacy and Efficacy of Public Opinion in a Post-Westphalian World.” Theory, Culture and Society 24.4 (2007): 7–30. [16] For further discussion of global memory and the transnational public sphere, see Rosanne Kennedy, "Moving Testimony: Human Rights, Palestinian Memory, and the Transnational Public Sphere," in Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney (ed.), Transnational Memory Circulation, Articulation, Scales, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and Boston, 2014: 51-78. Other Posts in this ForumThis post is part three of a four-part forum: "Transnational Memories: Sites, Knots, Methods." An earlier version was presented as part of a roundtable at the Modern Language Association's 2015 Convention in Vancouver that featured Rosanne Kennedy, Ann Rigney, Michael Rothberg, and Debarati Sanyal. In October 1998, a battle took place near Van in eastern Anatolia between the Turkish Army and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (the PKK). In many ways this was an “ordinary” battle in an area some consider North Kurdistan. Over the course of the 1990s, the Turkish state waged a brutal war of counter-insurgency against Kurdish militants that killed tens of thousands of fighters and civilians, destroyed thousands of villages, and displaced as many as a million people, all while denying the substantial minority of Kurds in Turkey basic human rights to language, culture, and political representation. The PKK, considered a terrorist organization by the European Union, the US, and Turkey, has fought for decades in the name of Kurdish independence and autonomy. A certain liberalization and de-escalation of the crisis within Turkey occurred in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and the reputation and political program of the PKK have been undergoing significant change. Yet, the Kurdish question remains an unresolved flashpoint in Turkey and the region, as recent fighting near the Turkish border in Syria and Iraq and the highly visible resistance in Kobanê make clear.  Wolf as Kurdish martyr Wolf as Kurdish martyr The battle in October 1998 ended as many did, with the army capturing and, it seems, summarily executing a number of the Kurdish fighters. Among those executed fighters was one who would become an icon of the Kurdish cause: Sehît Ronahî—Martyr Ronahî—from the YAJK, the women’s brigade of the PKK. While the iconography of Kurdish martyrs is extensive—and includes many women who have fought with this secular, revolutionary movement—Sehît Ronahî represents an unusual case. Ronahî was born in Munich in 1965 and was known by her birth name, Andrea Wolf, before she joined the PKK in the mid-1990s. Previous to enlisting in the women’s brigade, Wolf had been involved in radical left politics in Germany, had served time in jail, and may have been affiliated with the Red Army Faction. Her experience in the radical left—and possibly the threat of returning to prison—eventually moved her to align herself with the Kurdish cause. In this short paper, I want to use the unexpected, but not unique, case of Wolf/Ronahî to reflect on some of the issues central to our roundtable. As a non-national who died in the national liberation struggle of a people long denied a nation-state, Wolf provides an occasion to reflect on memory and politics within and across borders. Her case challenges us to examine the status of lieux de mémoire beyond the context of the nation-state; the relevance of migration, media, and diaspora to memory studies; and the political and methodological implications of the transnational turn.  The tomb for Wolf and forty other PKK militants The tomb for Wolf and forty other PKK militants It would not be an exaggeration to say that, in the years since her murder, Wolf has been transformed into a transnational lieu de mémoire that condenses an array of not-entirely-compatible currents. In addition to being a martyr for Kurdish national liberation, Wolf has become both a symbol of socialist internationalism and an object of human rights campaigns by Turkish, German, and European organizations. Various groups claiming allegiance to Wolf’s legacy have commemorated her death in multiple sites by constructing what Astrid Erll would call a “plurimedial” constellation of memory. In 1999, at the PKK’s yearly convention, the party voted unanimously to make Wolf a symbol of internationalist struggle, and her memory remains central to the Kurdish cause. In 2013, two years after a Turkish human rights organization discovered a mass grave holding Wolf’s remains along with those of forty other militants, a massive tomb in the region near Van where she died was named in her memory. Speaking at the tomb’s dedication ceremony in Çatak, a Kurdish guerilla evoked Wolf as “a manifestation of the diversity and internationality of the Kurdish movement.”  Commemorating Wolf in Berlin Commemorating Wolf in Berlin At the same time that Wolf circulates in the transnational Kurdish region, her memory has also remained present in Germany. There her story and image have been memorialized and remediated in books, posters, exhibitions, ceremonies, street demonstrations, and videos—most of them produced or organized by coalitions of radical German leftists and Kurdish activists in Europe. But her memory remains alive even in the mainstream press; a recent report in the Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel evoked Wolf while discussing the suddenly fashionable topic of Kurdish women fighters in Kobanê.  ABSTRACT: Traveling Images ABSTRACT: Traveling Images Finally, at an angle to both radical and mainstream currents in Germany, the internationally known artist Hito Steyerl—who was Wolf’s friend as a teenager in Munich—has produced an ongoing series of videos, essays, and performances that reflect on Wolf’s engagement with the PKK and mourn her death at the hands of the Turkish army. Videos such as November (2004) and Abstract (2012) constitute a requiem for internationalism, an interrogation of what she calls “traveling images” of revolutionary martyrdom, and an indictment of contributions by the German state and multinational corporations to the Turkish war against the Kurds. Steyerl begins her aesthetic engagement with Wolf’s memory by asking how a German “friend” can become a Kurdish “terrorist.” But Steyerl’s attempt to answer this question takes a self-reflexive turn as she realizes that she has herself in some fashion become, through her work, a “Kurdish protestor” and that the art world in which she moves is itself implicated in the transnational economies that produce the military technologies that killed Wolf. What can we make of this heterogeneous mnemonic activity, which I have only superficially evoked, and how does it help us think anew about transnational memory? Many of us have criticized Pierre Nora’s lieux de mémoire project for the way it remains within a nation-state framework and purifies the nation of colonial, postcolonial, and minority memories. Yet, Nora’s paradigm does help illuminate this case study. As Ann Rigney has often pointed out, lieux de mémoire make available an impressively flexible methodology because they highlight centripetal, condensed meanings along with the possibility of centrifugal ongoing metamorphosis. Following Rigney, we might say that this combination of condensation and displacement also has the potential to speak to the transnational work of memory. In this case, the mnemonic figure of Wolf-as-Ronahî condenses Kurdish nationalist aspirations, radical internationalist ideologies, and mainstream Euro-American fears about Third World terrorism. At the same time, those meanings demonstrate the possibility for mnemonic metamorphosis, as the recent reactivation of Wolf’s memory in the context of Kobanê exemplifies. But the Wolf case also reveals the limits of Nora’s project. If, as he puts it in “Between Memory and History,” the “differentiated network” of memory sites ultimately operates at the level of “national history,” then the conditions of possibility for Wolf to become a lieu de mémoire lie, as I have tried to indicate schematically, in the interaction of activities at a series of scales: between national aspirations, state repression, diasporic political organizing, histories of internationalist solidarity, and transnational media—a mixture that pushes the limits of the metaphor of the “site,” no matter how flexibly we conceive it. Steyerl’s notion of “traveling images”—which anticipates Erll’s notion of “traveling memory”—may be more evocative. Wolf’s story also complicates the linear narrative of continuously eroding “real” milieux de mémoire central to Nora’s project. Despite—or perhaps because of—the fully globalized context that made Ronahî possible and that has nourished her rise to iconic status, “real” communities continue to cluster around her memory sixteen years after her death: both in the Kurdish struggle and in extreme left milieus in Germany. But this case study also poses challenges to the emergent transnational memory studies that has arisen in response to Nora and what Erll calls the “second phase” of memory studies. Most important, from my perspective, it requires that we think more imaginatively about the status and scale of the political in memory studies. Nora’s focus on the nation retains plausibility because the nation-state continues to function as a memory-wielding agent of legitimation, discipline, and identity formation. Thus far, the primary referent for memory politics beyond the nation has been human rights, as Rosanne Kennedy discusses with great nuance in her contribution to this forum. As I’ve suggested, the discourse and practice of human rights do play a catalytic role in the Wolf case. Yet, the human rights framework is insufficient to describe both the salience of Ronahî’s memory and the political aspirations it evokes. An alternate term also emerges from this material: I want to propose that internationalism retains power both as a memory and an aspiration. The concept of “internationalism” may seem passé, and it is certainly not innocent, but it best describes the tradition of long-distance solidarity for which the traveling memory of Wolf stands. Remembering Ronahî leads us across national boundaries; but it also leads us to confront the borders that still exist and that are themselves forms of violence and injustice—in Kurdistan and elsewhere. We need new internationalisms because we still live in a world of nations. Other Posts in this ForumThis post is part four of a four-part forum: "Transnational Memories: Sites, Knots, Methods." An earlier version was presented as part of a roundtable at the Modern Language Association's 2015 Convention in Vancouver that featured Rosanne Kennedy, Ann Rigney, Michael Rothberg, and Debarati Sanyal.  Mural in Derry, depicting iconic photograph of Bloody Sunday 1972 Mural in Derry, depicting iconic photograph of Bloody Sunday 1972 On Sunday 30 January 1972, a paratroop regiment of the British army killed 13 participants in a civil rights demonstration in the Northern Irish city of Derry; a 14th victim died later. This event has come to be known as ‘Bloody Sunday.’ It has been remediated time and again since 1972: in literature, theatre, cinema, the visual arts, music. It has been the subject of memorials, and of two major judicial inquiries, one of which (the Widgery report of 1972) exonerated the army of all blame, while the other (the Saville report of 2010) acknowledged almost four decades later that their actions were “unjustified and unjustifiable,” an admission of culpability that lead to an official apology on the part of the British Prime Minister in that same year. The desire to see justice served with regard to this atrocity has been an important motor behind the intensity with which it has been remembered. As a result of all this attention, the significance of Bloody Sunday has extended beyond the particular city in which the atrocity occurred to become a shorthand for the long-term struggle of the catholic minority for civil rights in Northern Ireland as a whole. Bloody Sunday has thus become a classical ‘site of memory’ in Pierre Nora’s sense, a site-specific and locally-experienced event that stands for itself and, by a process of condensation and displacement, for much more besides.[1] What exactly it stands for is open to debate, and this polyvalence is arguably part of its resilience as a site (see further Rigney 2015).[2] What concerns me here today, however, is less how Bloody Sunday was remembered in Northern Ireland than its position within a larger, transnational field. The chances are that many of you reading this will also ‘recall’ Bloody Sunday, if only thanks to Paul Greengrass’s Bloody Sunday (2002) or U2’s Sunday Bloody Sunday (1983). For if Bloody Sunday is a site-specific, locally-inflected memory site bound up with the city of Derry, it is also an example of what Astrid Erll (2011) has called a ‘travelling memory’ that operates across different national borders with the help of its mediations.[3] Bloody Sunday did not just become a transnational memory after the fact, however: it has always already been transnational. Bloody Sunday belonged, and was perceived from the outset as belonging, in what might be called a ‘canon’ of atrocities – many of which are called Bloody Sunday too - in which a peaceful demonstration by citizens is violently suppressed by state forces. These events are specifically related to the modern conditions of urban living as well as to the political condition of democracy, or would-be democracy, in which the will of the nation aspires to be represented in the workings of the state. The first Bloody Sunday to be named as such took place in Trafalgar Square in 1887. This involved the brutal breaking up of a march for civil liberties in which a coalition of socialists, workers organisations and Irish nationalists took part. Exactly a year later, this first Bloody Sunday was commemorated in a new mass gathering in London, which was also connected through a gesture of internationalist solidarity to the first anniversary of the deaths of the so-called Chicago Martyrs. It would appear that the mass shootings of demonstrators in St. Petersburg in 1905 was subsequently called ‘Bloody Sunday’ by analogy with the one in Trafalgar Square. There’s no time to go into details about these other ‘Bloody Sundays’, including the ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Dublin in 1920 and at Selma in 1965. Most important here is the fact that multidirectional comparisons between these various outbursts of state violence were very common on the part both of participants and observers.[4] As the Dublin-based Irish Times wrote in reaction to the atrocity in Derry, for example: “Sharpeville, Amritsar, Bloody Sunday 1920 – the parallels are inadequate” (31 January 1972). So from the get-go the 1972 Bloody Sunday resonated with outrages that had taken place elsewhere. I use the word resonance here deliberately as a way of designating particular linkages between events that are not based on chronological connections, but on systemic similarities that work across space and time. ‘Bloody Sunday’ is an event-type that, like a mnemonic wormhole, connects locations, more specifically, cities across the world. The result is a multi-sited, city-to-city memory that invites us to think of transnationalism not merely as a broadening of geographical scale but as a rethinking both of scale and of the relations between distance and proximity.[5] Each ‘Bloody Sunday’ is a singular event at the same time as it is grafted onto the memory of other civilian massacres in other cities as these have travelled through the international media and the arts.  ‘Bloody Sunday,’ Selma 1986 ‘Bloody Sunday,’ Selma 1986 The perceived resonances between these multiple Bloody Sundays is enhanced by the visual record where the underlying drama of ‘citizens in action’ becoming victims of state violence is performed over and again in iconic images that capture the movement of the crowd, as they first assert their right to demonstrate and then have to flee from violence. This ambivalent combination of victimhood and agency seems to feed into the mobilizing power of such images, exemplifying Aby Warburg’s concept of Pathosformel (Pathosformula), a visible constellation that arouses both deep memory and deep affect.[6] So what sort of general issues can we distill from this very briefly presented example? Three interrelated things come to mind that bear on the issue of transnational memory and which are central to my research in progress. To begin with the case serves as a reminder that the transnational movements of memory are not a recent phenomenon, though transnationalism as an analytic perspective may be. Nation-building has always stood in tension with the movement of ideas, stories, and images across borders – with the help of media but also regularly supported by the actions of groups and individuals with a self-consciously internationalist agenda working to make common cause with people elsewhere. Recuperating the archive of such transnational entanglements will allow cities and the civic, rather than nations, to take centre stage in our analysis and help us go beyond methodological nationalism while still giving due account to the role of the state. Secondly, the case challenges cultural and literary studies to account more precisely for the movements of memory across borders – what gets remembered, picked up elsewhere and how? Judging by the resilience of ‘Bloody Sundays’ in the visual and textual record, there is something particularly potent about the combination of state violence and the right to protest. The ‘stickiness’ of these events in cultural memory, the fact that they are recalled over and again, could at least in part be explained by their melodramatic form.[7] A Bloody Sunday involves the dramatic conversion of scenes of innocence and hope into scenes of brutal repression. The result is a double-faced, literally outrageous figure of memory that dramatizes the ideals and shortcomings of democracy in a melodramatic form, encapsulating both the agency of citizens (as evidenced in their power to demonstrate and to flee) and the limits of that power in face of the state. In the future we need a greater understanding of the role of such aesthetic forms in mobilising people, both within and beyond state borders, and for particular causes and not for others. Finally, the case of Bloody Sunday challenges us to think more about, or to think in new ways, about the relationship between activism and memory, building further on Kristin Ross’s work on the afterlives of 1968.[8] Certainly in the cases briefly considered above memory and activism are deeply entangled: the commemoration of the outrage feeds back into the broader struggle to which the original demonstration already belonged – be this the struggle for workers’ rights or for national liberation. Distentangling the commemoration-activism nexus might help us move beyond the over-emphasis on the traumatic in memory studies and to think more clearly about the ways in which remembering the past, acting in the present, and shaping a different future have worked together, and continue to do so, across national borders. [1] Nora, Pierre, ed. 1997 [1984-92]. Les lieux de mémoire. 3 vols. Paris: Gallimard. [2] Rigney, Ann. 2015. "Do Apologies End Events? Bloody Sunday, 1972-2010." In Afterlife of Events: Perspectives on Mnemohistory, edited by Marek Tamm, 242-261. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [3] Erll, Astrid. 2011. "Travelling Memory." Parallax 17 (4): 4-18. [4] Rothberg, Michael. 2009. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [5] See also De Cesari, Chiara, and Ann Rigney, eds. 2014. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Berlin: De Gruyter. [6] Hurttig, Marcus Andrew. 2012. Die entfesselte Antike: Aby Warburg und die Geburt der Pathosformel. Köln: Walther Hönig. [7] Brooks, Peter. 1995 [1976]. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [8] Ross, Kristin. 2002. May ’68 and its Afterlives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Other Posts in this Forum |

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed