|

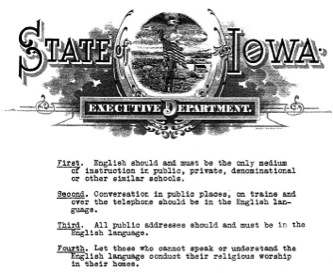

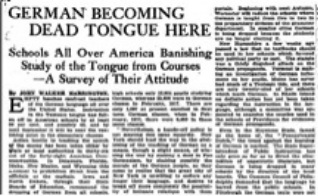

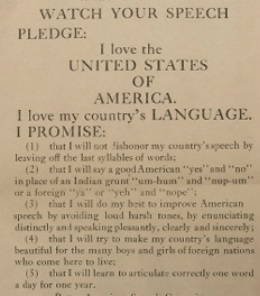

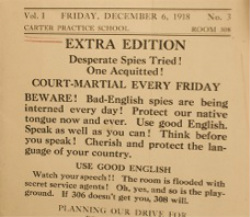

This semester the University of Illinois is marking the centenary of World War I with a faculty-led, cross-campus initiative, The Great War: Experiences, Representations, Effects. During the course of the semester Days and Memory will be publishing a series of posts related to the war. We are pleased to continue this series with Dennis Baron's reflections on the impact of World War I on language policy in the United States. By Dennis Baron In April, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. In addition to sending troops to fight in Europe, Americans waged war on the language of the enemy at home. German was the second most commonly-spoken language in America, and banning it seemed the way to stop German spies cold. Plus, immigrants had always been encouraged to switch from their mother tongue to English to signal their assimilation and their acceptance of American values. Now speaking English became a badge of patriotism as well, a way to prove that you were not a spy. The war on language was fought on two fronts, one legal, the other, in the schools. Its impact was immediate and long-lasting. German was the target, but the other “foreign” tongues suffered collateral damage. Immigrant languages in America went into decline, and there was a precipitous drop in the study of foreign languages in US schools as well. Speak English, it’s the law Boycotting German was the first step in the campaign, but legislating against the language quickly followed. Scribner’s was urged to publish no German titles during the war. Sheet music dealers refused to handle German songs. At least one American Berlin was renamed Liberty. Even German foods were rebranded. Just as later, during the Iraq War, French fries would become freedom fries, in the America of World War I, German fried potatoes became American fries, sauerkraut morphed into liberty cabbage, and superpatriots even caught the liberty measles. In addition, new laws regulated the use of foreign languages. Responding to a growing sentiment that using anything but English gave aid and comfort to the enemy, the Trading with the Enemy Act (50 USC Appendix), passed in June, 1917, suppressed the American foreign-language press and declared non-English printed matter unmailable without a certified English translation. Across the country, state and local ordinances forbade the use of foreign languages, urged immigrants to switch to English immediately, and punished those who failed to comply. On May 23, 1918, Iowa Gov. William Harding banned the use of any foreign language in public: in schools, on the streets, in trains, even over the telephone, a more public instrument then than it is today. For Harding, the First Amendment “is not a guaranty of the right to use a language other than the language of this country—the English language.” Harding’s English-only order covered freedom of religion as well: “Let those who cannot speak or understand the English language conduct their religious worship in their home.” And he told one reporter, “There is no use in anyone wasting his time praying in other languages than English. God is listening only to the English tongue.” Speaking in Des Moines five days later, former president Theodore Roosevelt endorsed Harding’s “Babel Proclamation,” introducing a phrase that would become a refrain of today’s official English movement: "America is a nation—not a polyglot boarding house. . . . There can be but one loyalty—to the Stars and Stripes; one nationality—the American—and therefore only one language—the English language." Such attitudes had a chilling effect on language use. 18,000 people were charged in the Midwest with violating the various new English-only statutes. Many of the wartime English-only laws were later repealed or allowed to expire. But the decline in non-English languages in America that they initiated continued, reinforced by postwar immigration reform. Responding to a new wave of isolationism, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, slowing immigration from the nonanglophone countries of Europe to a trickle and denying admission to nonanglophones from just about everywhere else (Asians were banned completely, and in the debate over the bill, Jews were singled out as particularly unassimilable). When immigration re-opened again in 1965, Americans who, after more than 40 years of “reform” simply assumed that their country had always been monolingual, reacted to the new, unfamiliar immigrant languages by declaring English endangered, attacking bilingual education, and passing new laws making English the official language of government, the workplace, and the schools. Speak the language of your flag The schools opened up a second front in the Great War on foreign languages in World War I America. In 1918, the New York Times reported that as many as 25 states had already removed German from the curriculum, an action the newspaper applauded as “a matter of polity, of patriotism, of Americanism” and “good hard common sense.” Schools banned foreign-languages from classrooms and schoolyards, promoting English not just as the best way to succeed in life, but also as the language for patriots. In 1918, the Chicago Woman’s Club launched Better American Speech Week to further this agenda. With slogans like “Speak the language of your flag”; “American Speech means American loyalty”; and “Better Speech for Better Americans,” children were encouraged to learn English, and those who already spoke the language were asked to speak it better. Schoolchildren had to take a “Watch Your Speech” pledge which began, “I love the United States of America. I love my country’s language,” and included among its promises, “that I will say a good American ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in place of an Indian grunt ‘un-hum’ and ‘nup-um’ or a foreign ‘ya’ or ‘yeh’ and ‘nope.’” Better American Speech Week reflected the spirit of wartime American, encoding patriotism, the assimilation of immigrants, and a rejection of minority languages and dialects. It resonated with popular opinion and was embraced by schools and by the press from coast to coast. In addition to pledges and posters, schools recruited students to spy on the usage of their peers. Those caught committing crimes against the language were interned, hauled before student tribunals certain to convict them, and made to wear signs testifying to their shame. Exposing the enemies of English was the least that children could do while their parents were busy exposing the enemies of the state. After the war the US Supreme Court threw out laws in Nebraska and Iowa banning foreign-language education (Meyer v. Nebraska [262 US 390] 1923), but the damage was already done. Before World War I, 25% of American high school students studied German. By 1922, that figure had plummeted to 0.6%, a level from which it never recovered. World War II did not see the same language restrictions as World War I, and by then learning the language of the enemy rather than banning it had become an important tool for national security. Still, in 1948, only 0.8% of American students were studying German in high school.

The War to End All Wars failed to do that. But the Great War on language that began in 1917 rages on despite having met its goals. Today, with immigrants abandoning their first languages faster than ever and foreign-language enrollments still precarious, many Americans still regard English, and therefore America, as under attack. States like California and Arizona, where ongoing immigration still creates large numbers of minority-language speakers, ban bilingual education in the mistaken belief that this will hasten the switch to English, and Iowa, where only 3% of residents speak a language other than English (and many in that number speak English as well), revive the Babel Proclamation and declare English the state’s official language to save it from imminent destruction. American culture has always been hostile to foreign languages, and to native languages that aren’t English, so even without World War I, we still wouldn’t be celebrating National Heritage Language Day. But even though the war didn’t make the world safe for democracy, it did its bit to make the country “safe” for English.

0 Comments

|

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed