|

By: Helen Makhdoumian and Claire Baytas On October 9th, 2017, the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies (HGMS) hosted a campus screening of the 2016 documentary The Destruction of Memory, directed by Tim Slade and narrated by actress Sophie Okonedo. A conversation via Skype between Slade and audience members from across the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign campus followed the screening. The screening of this exigent film, which invites its viewership to closely consider the relevance of what Raphael Lemkin once termed the “cultural” dimension of genocide: the destruction of cultural property, and the Skype discussion could not have come at a better time. During Fall 2017, Professor Brett Kaplan taught the Introduction to Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies graduate seminar. Members of our interdisciplinary class, many of whom will present at the upcoming One Day Graduate Symposium in Memory Studies on campus this April 6th, 2018, engage with the histories, legacies, and memories of diverse traumatic events in different national contexts, past and present. Broadly, then, the documentary offered us another avenue to grapple with some of the questions that we recurrently raised in class. That is, we regularly discussed the politics, stakes, and potentials that working comparatively within the fields of trauma and memory studies affords and the codification of terminology that informs processes of identifying, historicizing, and adjudicating acts of mass violence. In what follows, we will focus our reflection on the documentary around some of its comparative gestures. Before we do so, however, we want to provide a brief overview of the film. Specifically, Slade’s documentary is based upon Robert Bevan’s book, entitled The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War (2006). Bevan, a widely-published journalist, architecture critic for The London Evening Standard, and member of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, examines in his book a variety of cases of war and conflict during which physical structures of cultural and historical significance were razed to the ground. Slade’s documentary walks its viewership through a selection of historical instances analyzed in Bevan’s book, employing video clips, photographs, and interviews with witnesses, scholars of genocide, and experts on cultural heritage sites. A few case studies examined in the film include the Siege of Sarajevo in the mid-nineties, the bombing of Germany during the Second World War, and the actions of the self-proclaimed Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Slade’s juxtaposition of case studies of cultural destruction—or the annihilation of irreplaceable artwork, artifacts, and historical sites—in the 20th and 21st centuries comes to the fore as the documentary’s primary comparative gesture. Indeed, the film begins with a series of clips in which interviewees articulate the purpose of perpetrators’ deliberate destruction of cultural property before, during, and after presumably historically-bound acts of mass violence. This includes the words of Simon Maghakyan, an Armenian American educator and activist, who draws upon the history of the Armenian Genocide to assert, by “targeting monuments,” for example, “you are oppressing the people and making it easier to get rid of them, not just to wipe out their physical record and make it impossible for them to return, but also using it as a weapon.” We will later discuss in more detail the effects of the film’s return to such arguments, which it does by situating collective traumatic histories and ensuing memory work in conversation. For now, we want to map another key conceptual knot of connection that percolates throughout the film and manifests most legibly when Okonedo states in her voiceover regarding a trial judgment as part of the proceedings for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), “The voice of Lemkin could be heard distantly returning.”[1] This comment about the pertinence of Lemkin’s words also welcomes audiences to recall the beginning of the documentary, which prepares viewers to ask the following of the temporally and spatially distant yet intimately linked contexts that the film ultimately references: how do these histories lend themselves to a call for an expansion of definition of the term “genocide” to include a key component Lemkin originally proposed? Indeed, the documentary illuminates that while the United Nations General Assembly formally adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide on December 9th, 1948, the definition of genocide in legal terms is best understood when seen as a culmination of years of efforts by Lemkin and when situated within a larger trajectory of declarations on the laws of war and war crimes within international law. In this vein, the documentary illuminates that clauses to protect cultural property in times of war were introduced in early twentieth-century peace conferences, such as in The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the inclusion of wanton destruction of cultural property as part of a list of 32 individual criminal acts identified by the Commission on Responsibility of the Authors of War, which was created by victorious Allies to investigate allegations of criminality against the leaders of the defeated German and Ottoman Empires.[1] While the documentary, like others, goes on to note how the failure to prosecute the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide informed Lemkin’s conceptualization and coinage of the term “genocide,” it departs from others by seemingly arguing for 1933, 1944, and 1946 as years just as defining as 1948 (if not more so) in the genesis of the term “genocide.”[2] At a League of Nations legal conference in 1933, historian of genocide Dirk Moses explains, Lemkin proposed the prosecution of two new international crimes: “vandalism” (attack on cultural property) and “barbarism” (what we would now call genocide, physical attacks on peoples). States in the League of Nations at that time declined to criminalize these kinds of acts and in 1944, Lemkin used “genocide” as a single term for what he earlier called barbarism and vandalism. Shortly after, in 1946, early drafts of the genocide convention, commissioned by United Nations General Assembly, defined genocide as one of three acts: physical, biological, or cultural genocide. The United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand objected to the inclusion of a cultural dimension because, as Moses asserts, they “worried about the fallout from their treatment of indigenous peoples and their cultures.” Thus, with the exclusion of cultural elements, the 1948 convention remains “essentially what Lemkin proposed as barbarism in 1933.” By “reading” what is present in the 1948 convention in relation to what is absent from Lemkin’s original proposals and the repercussions of this removal, The Destruction of Memory prepares audiences to contend with the implications of arguments presented through Okenodo’s voiceover about succeeding legal documents that address attacks on cultural heritage and property. These include the ruling of appeal judges in the ICTY in April 2015 that targeted cultural destruction cannot be considered as evidence of genocide nor possibly even intent of genocide, the citation of “military necessity” to cloud intent, the lack of recognition of the intents to suppress the culture of groups as a matter of human rights despite arguments during the adoption of the 1948 convention that this question would one day be dealt with as such, and the need to protect cultural heritage more than through a document such as the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict that is bound by the rules of war. In so doing, viewers are deliberately left to imagine the potential repercussions of, as Bonnie Burnham, President Emirata of the World Monuments Fund, posits, recognizing cultural heritage destruction as a crime against humanity and as Bevan asserts in an interview in the documentary, inserting those vandalism clauses back into the 1948 genocide convention. One way in which The Destruction of Memory emphasizes the significance of taking into consideration attacks on cultural heritage and property within the study of genocide and mass violence is through the connections the documentary makes between the numerous case studies it examines. The manner in which The Destruction of Memory links the variety of historical events with which it engages is not done arbitrarily: the film leaves its viewership with a few key impactful messages as a result of its comparative approach. Firstly, the documentary underlines the repetitive nature of the strategies employed by those who set out to eradicate a certain group of people. One can notice across the different cases mentioned in the film that the eradication of objects and/or buildings representative of the targeted group’s culture and history is an often carefully arranged dimension of the overall plan of genocide. However, it is not just the ways in which genocide and acts of mass violence are plotted and carried out that are portrayed as symptomatic of a common phenomenon. The Destruction of Memory furthermore demonstrates that the underlying intentions of the perpetrators when they plot to destroy cultural property tend to be similar: they are fueled by motivations such as launching a symbolic attack on a group’s collective identity or disseminating fear and intimidation. During the lengthy interview with Bevan that appears in the film, he explains the “carpet bombing” of Germany by the Allies during the Second World War as “clearly a tactic to attack historic cities… [in order to] to demoralize people.” Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels’ diaries are subsequently quoted by Okonedo to reveal that the Axis powers had similar intentions. “Like the English,” Goebbels proclaimed, “we must attack centers of culture… such centers should be leveled to the ground.” This point is driven home even further with regard to the Croat-Bosniak War of the 1990s, when the film recalls Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic’s words from her elegy to the Mostar Bridge. Yet again, an attack on a physical structure is described as an attack on identity: “because [the bridge] was the product of both individual creativity and collective experience, it transcended our individual destiny… the bridge was all of us, forever.” In each case study, the desires of those committing the crimes and the willful nature with which they commit them are clearly portrayed to be similar across time and space. The Destruction of Memory thereby traces the common threads in perpetrator practices for its viewership, demonstrating the unsettling ways in which many aspects of the implementation of genocide tend to repeat themselves throughout history. The documentary’s manner of connecting these different events furthermore serves to blur the line between the past and present for its viewers. This is a result of the fact that the film touches upon both historical and contemporary instances of destruction of cultural property, suggesting that all are trends of the same phenomenon. As a result, when learning about these attacks on symbols of culture during genocide or war that occurred decades ago, the film’s viewership cannot simply disregard these events as tragic losses of the distant past. The documentary mentions both at its beginning and examines in more detail towards the end contemporary instances in which the Islamic State is acting to eradicate objects and sites representative of cultural heritage. The group’s annihilation of the Tomb of Jonah in 2014 and their looting, damaging, and destroying artifacts of the Mosul Museum in 2015 are but two of the examples highlighted in the film. Therefore, although certain precious artifacts or structures of the past may already be lost, the film makes it clear that plans to eradicate materials of cultural and historical relevance in certain areas are still being carried out and will continue to be in the future. The Destruction of Memory thus encourages its viewership to recognize the continued significance of the destruction of cultural property as well as the importance of speaking out against such acts. One of the many intriguing avenues for future reflection that The Destruction of Memory opens up for us as viewers is inquiry into the ethics of studying the cultural dimension of genocide. Professor Brett Kaplan posed a question on this very subject to Slade during the question and answer session that followed our October 9th screening, asking whether he found it morally problematic to produce a film that gives more screen time and attention to the loss of objects, buildings, and other structures during genocide than it does to the loss of human life. One could, on the one on hand, take issue with the filmmakers’ choice to focus at length on critiquing violence against physical edifices rather than violence against human beings, which was simultaneously occurring during these moments in history cited in the film. On the other hand, it can also be argued that this documentary portrays the different dimensions of genocide as closely interconnected. As previously quoted, Maghakyan for one qualifies “targeting monuments” as a “weapon” against people and as an act of “oppression.” Early in the film, Okonedo lingers upon Lemkin’s words on this same subject: “physical and biological genocide,” Lemkin claimed, “are always preceded by cultural genocide or by an attack on symbols of the group.” The film thereby also proposes that the destruction of cultural property can serve as an indicator of a broader plan to eliminate an entire people, which begins with the elimination of the physical proof of that people’s history. We thus conclude by proposing that how one understands and chooses to represent the links between violence against human beings and cultural heritage broadly construed is a matter open to debate. It is this type of conversation—challenging, yet important on an ethical level—that The Destruction of Memory will serve to incite among its viewers. With each screening, Slade’s documentary will reopen discussions concerning the study of the different dimensions of acts of mass violence and genocide of our societies’ pasts, thereby promoting an enduring critical engagement with these crucial topics. [1] Okonedo quotes the following from a trial judgement: “Where there is physical or biological destruction, there are often simultaneous attacks on the cultural and religious property of the targeted group as well, attacks which may be considered as evidence of an attempt to physically destroy the group.”

[2] Specifically in the Commission on Responsibility of the Authors of War, under Chapter II: Violations of the Laws and Customs of War, the list includes “Wanton devastation and destruction of property” (item #18) and “Wanton destruction of religious, charitable, educational, and historic buildings and monuments” (item # 20). See the Commission on Responsibility of the Authors of War document here. For the Hague Convention documents, see here and here. [3] For a timeline noting the major and conceptual legal advances in the development of the term “genocide” see this page on the United States and Holocaust Memorial Museum website. For the text of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, see here.

1 Comment

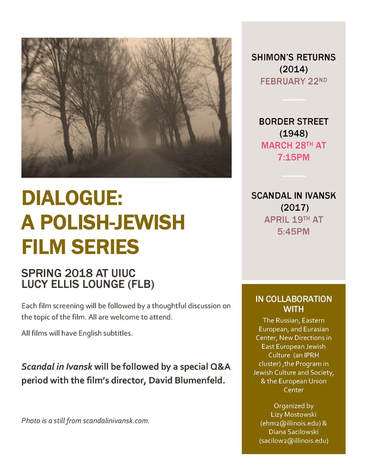

By Lizy Mostowski  I created Dialogue: A Polish-Jewish Film Series about a year ago with the intention of starting a forum for cross-cultural dialogue around Polish-Jewish issues that extend well beyond the scope of this particular cultural space. The goal of the Series is to breakdown perceived binaries between “Polish” and “Jewish” cultures through dialogue and discussion about a film. I was inspired by Professor Erica Lehrer’s exhibition Souvenir, Talisman, Toy put on at the Seweryn Udziela Ethnographic Museum in Krakow, Poland in 2013 where Prof. Lehrer attempted to create cross-cultural dialogue through her exhibition featuring wooden figurines of Jews carved by Poles after the Second World War. Each of my screenings begins with a film (sometimes a particularly controversial film) on a Polish-Jewish topic and is followed by a discussion led by graduate students specializing in the area. This academic year, Diana Sacilowski and I have curated the lineup of films and together we introduce and discuss the films with participants. In past semesters, we have screened films like Aftermath (2012), Ida (2013), Austeria (1982), and Little Rose (2010). Our first screening this semester was the largely independently produced documentary film entitled Shimon’s Returns (2014). The film is directed by US-based Polish-Jewish filmmakers Katka Reszke and Slawomir Grunberg—both of whom have been vital in many grassroots Jewish revival efforts in Poland. The film allows a glimpse into the life of a man named Shimon Redlich, an Israeli historian and child Holocaust survivor. In 1948– before emigrating to Israel, Shimon was cast in Unzere Kinder–Poland’s last ever Yiddish feature film. In four languages—English, Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew—Shimon guides viewers through his story and his recurrent visits to contemporary Poland and Ukraine. Diana introduced the film, suggesting that, “various critics have noted, despite the dark history the film contends with and how charged the topic of the Holocaust is in this region of the world as of late, particularly regarding issues of complicity and who helped and who participated, the documentary itself is fairly uplifting.” The film seems to have been created to speak to a North American audience as Shimon narrates to the camera only in English while his interactions with others throughout the documentary occur predominantly in Polish and Hebrew. The film complicates common stereotypes around Polish-Jewish relations after the Holocaust. As one participant noted in the post-film discussion, it is as though there is a dramatically swinging pendulum between scenes that illustrate pro-Polish and anti-Polish sentiments in Shimon’s interactions and experiences in his returns to Poland throughout the documentary. For example, in one scene Shimon approaches a right-wing group who are dressed in Nazi uniforms in Lwow (which was a part of Poland before the Second World War), yet instead of overtly confronting them, Shimon climbs up on a Nazi motorcycle and pretends to ride it. In another scene, Shimon meets his childhood sweetheart in Lodź, where they ride in a cycle-rickshaw and reminisce about their youth in the city, organically alternating between Polish and Hebrew. In this way, the film may seem to reinforce preconceived stereotypes that a North American viewer might carry with them before seeing the film, such as a notion that all Poles are anti-Semitic because of the complicity of some Poles in the Holocaust or that Poland was a thriving (Yiddish) Jewish homeland before the Holocaust (think of the nostalgia produced by the American film Fiddler on the Roof (1971)), but in fact, the film reveals the complex texture of Shimon’s identity and relationship with Poland, Poles, and the past. Shimon’s Returns thereby shows that Polish-Jewish identity and Polish-Jewish relations after the Holocaust are likewise more nuanced and complex than many anticipate before viewing the film. It is important to note that Shimon’s Returns was made in 2014, before the introduction of the recent law which seeks to criminalize certain discourses on Polish complicity in the Holocaust. “On the one hand, this film might seem like it’s in line with new political discourse focusing on Polish heroism over complicity. But the story is far more complicated than that,” Diana rightly highlighted in her introduction to the film. In its complexity, Shimon’s Returns opens up a space for dialogue between perceived cultural boundaries that linger from the anti-Semitic laws of the Second World War and the Anti-Semitic Campaign of 1968. In our discussion we considered how such dialogue-initiating films may be at risk in light of the new policies implemented by Poland’s right-wing government and the extreme responses to them from the Jewish right-wing.

All are welcome to join us for the screening of Scandal in Ivansk (2017) on Thursday, April 19th at 5:45pm in the Lucy Ellis Lounge of the Foreign Languages Building (707 S. Matthews, Urbana) which will be followed by a special Q & A with the film’s director, David Blumenfeld, via Skype! |

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed