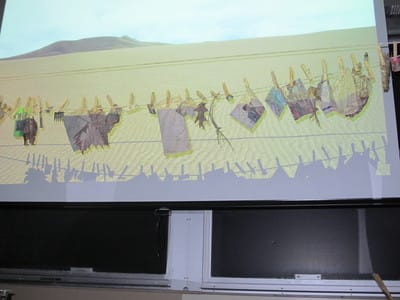

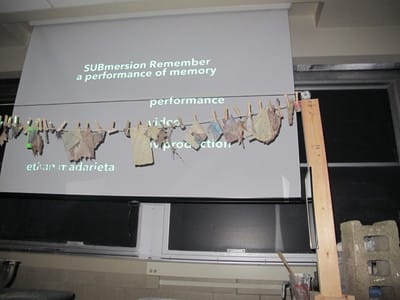

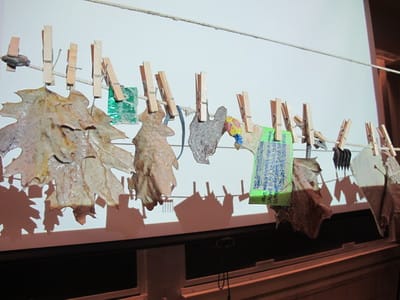

Disorienting Memory / Reorienting the Present A response to Ethan Madarieta’s SUBmerge Remember12/22/2016 By Comparative and World Literature Graduate Student Meagan Smith The smell of baking bread is an incredible, visceral memory trigger. It always takes me back to a particular time and place in my childhood, and then initiates an involuntary flood of other associations and memories. I’m at my best friend’s house; it must be sometime in the mid-nineties, when I was in middle school. It was around the time that those automatic bread-makers became popular and Patti, my best friend’s mom, had one. She’d make this slightly crusty white-bread and the smell would, of course, fill the kitchen and creep throughout the house. Our parents were close and Patti would have my whole family over for these wonderful dinners. My mom was just a shockingly terrible cook, so dinners at Patti’s house were always a treat for me and my siblings. The smell of baking bread always reminds me of Patti, who died about a year-and-a-half ago, just before her sixtieth birthday. It reminds me of being in middle-school; of the safety and comfort of my best friend’s house as opposed to the chaos and pins-and-needles feeling of my own house. For some reason, it also reminds me of the first time I ate fresh green beans. Maybe Patti served them with the bread at one of those wonderful dinners. The range of these personal details, the intense emotions and the inconsequential memory of the green beans, were all invoked and laid bare for my own private act of contemplation the night of December 9th during Ethan Madarieta’s performance titled, SUBmersion Remember: a performance of memory. Submersion is a fitting description of the experience. Ethan was the sole performer and didn’t speak a word or even make eye contact with the audience, but we were each engrossed in the sensorial textures he managed to create and the stream of individual memories and emotions he managed to raise in a span of roughly forty-five minutes. The lights were off, a mild psychedelic droning music played in the background, a video installation with shots of soft cumulus clouds and footage of sandy high-desert from a variety of angles played on a screen behind an apparatus consisting of a clothesline suspended between two cinderblocks and pine two-by-fours, and, to complete the sensorial submersion, the scent of baking bread filled the room from a convection oven in the corner. Ethan’s role consisted mainly of mixing and kneading the ingredients for a second loaf of bread while intermittently pausing to hang objects covered in batter from the clothesline. This was bookended with several minutes of him sitting on the cinderblocks, bent forward with his elbows on his knees in a sort of self-contained, introspective pose. The performance struck a balance between invoking this intensely personal, self-contained introspection—in which the actions, objects, and spaces presented to the audience remained unexplained—and the ambiguity of impersonal observation. In some sense the precise content and meaning of the more or less familiar images was less important than their common ability to invoke an individual response. This tension between the familiar and the strange, the intensely personal and the common or generalizable, hints at the theoretical apparatus of Ethan’s performance: the Bergsonian notion of “pure memory”. For Bergson, pure memory relies on the defamiliarization of the familiar. It can disrupt the automatic chain of involuntary perception and unconscious reaction. Perception, for Bergson, is as automatic as reflex and is full of memories that speed up the time it takes to involuntarily process external stimulus. The ease with which a stored memory is recalled and mapped onto a current moment overcomes the more complicated process of integrating perception and memory in response to a more or less familiar external object. In this process, the spontaneous potential of the individual body is lost, choice and even consciousness of one’s movement through the world become all but obsolete. To reintegrate the body into the external world of things acting upon it, we must disrupt mindlessness of actions produced by automatic, unconscious perception. The surreal act of hanging batter-soaked objects on a clothesline with no explanation accomplishes this act of disruption. Each of the memory-objects—photographs, leaves, little trinkets—represents some significant moment in Ethan’s life, but that significance is lost to the audience who likely cannot identify the object let alone access the memories associated with it. While each object might be familiar in a general sense, they are emptied of their specific content, they lack the context needed for interpretation, and they become strange and unfamiliar when obscured by the batter and the layers of indecipherable meaning heaped on them through their association with someone else’s inaccessible memories. The technique of making an object or event unfamiliar is intended to disorient rather than orient us to our perceived universe. It gives objects and even memories back their unique properties so that we can perceive them without all the baggage of always already “knowing” what they mean and how to respond to them. For an object or event to break the ceaseless automization of perception and reaction, though, the process of perception must be artificially prolonged. What Bergson calls “pure memory” is the process by which these automatic memory responses are disrupted, broken down, and then strung back together. This requires sustained intellectual engagement and full emersion in the sensorial experience of the disruptive event. What Ethan’s performance enacts is the duration of pure memory; he emphasizes the process, the time and full awareness it demands. He provides the audience with layers of sensory stimuli full of surreal but familiar memory triggers: the stream of personal associations invoked by scent of the bread, the prolonged submersion in the disorienting space of someone else’s memories, the strangeness of the batter-soaked objects hanging from the clothesline, and especially the otherworldliness of the clouds and open desert occupied only by an impersonal naked body leaving impermanent marks in the sand. For me, this last image is associated particularly with the imaginative futures and “elsewhere” of science fiction—a realm of unfamiliarity and untapped potential. It strikes me that the juxtaposition of all the memories and emotions invoked by the multiple layers of Ethan’s performance is full of the same surreal otherworldliness and untapped potential. Placing my childhood memories of my best friend’s house next to the perplexing image of batter dripping from unidentified objects on a clothesline in front of a video montage of a naked man walking in reverse through some alien sandscape is disorienting, to say the least. Throw in the random memory of green beans and we’ve certainly entered the realm of the surreal. That’s the point, though. Pure memory requires full, sometimes uncomfortable submersion, but it provides us with fresh perceptions and enough strange material to build otherwise impossible connections and to imagine brave new futures. Photos from the event taken by Professor Brett Kaplan

1 Comment

By HGMS Graduate Student Priscilla Charrat Nelson On October 19th, 2016, the Program in Jewish Culture & Society and the Department of French and Italian received the visit of Maxime Decout, Maître de conferences at the University of Lille 3 in France, and author of three books on the following topics: Albert Cohen, Writing Judaism in French Literature, and Bad Faith in Literature[1]. His visit focused on French author, and 2014 Nobel Prize recipient, Patrick Modiano. Decout is the editor of the special issue dedicated to Patrick Modiano of the journal Europe and published articles on Modiano, among other numerous publications on Albert Cohen, George Perec, Romain Gary, and Judaism in French literature[2].  A leading figure of contemporary French literature, Patrick Modiano’s reception of the Nobel Prize in 2014 came to the surprise of the American media and readership, despite the author’s literary fame in Europe. The relatively restrained circulation of Modiano’s work in North America before the reception of his Nobel compared to his European success might be due to the topographic nature of his works, which follow the paths of characters through Paris’s sinuous streets, evoking the social background of characters by mentioning the name of neighborhoods in passing, and inviting the reader to tap into his own knowledge of the places evoked. The serpentine nature of the Parisian landscape that echoes the meandering of memory evoked by Modiano’s novels might more intuitively translate culturally to European readers than to Americans more used to the grid system of American city planning. Modiano’s success is due largely to the singularity of his approach. In the midst of instant communication and flash news, Modiano proposes novels which posit the void, and the enigma, as value. Maxime Decout started his visit with a workshop on Modiano’s best known, and most accessible, novel Dora Bruder. The novel follows a narrator, an apparent double of the author himself, a teenage Jewish runaway living in Paris during the Occupation. The novel’s artfulness lies in the way it engages the reader, proposing a narrative permeated with silence, restraint, and interrogation that leads the reader to piece together clues both about Dora herself, and about the lived experience of Jews in occupied France.  Maxime Decout Maxime Decout A specialist of Judaism and Jewish identity in French literature, Decout highlighted the absence of an identifiable Jewish literature category in France. While there are French Jewish authors, and while some of them might write about Jewish identity, Jewish History, or Jewish protagonists, Decout pointed out that unlike in American literature, there is no "French Jewish" canon. Modiano might write about the Jewish runaway Dora, but he can also be described as a writer of the occupation period, a writer of Paris and its suburbs, or a writer of silence. Yet, the Occupation period recurs obsessively in Modiano’s work with many of his novels echoing each other through recurring scenes, anecdotes, or motifs such as phone books listing names and addresses, photographic portraits, and suitcases (tacitly alluding to the Holocaust). Born in 1945 to a Sephardic Jewish father and a gentile Belgian mother, Modiano’s own Jewish identity remains a constant questioning on inheritance best apprehended through his body of works. We thank Dr. Decout for his superb talk and workshop, and pledge to follow Modiano’s footsteps in our continuous engagement with memory and literature. [1] -Albert Cohen : les fictions de la judéité, Paris, Classiques-Garnier, « Etudes de littérature des XXe et XXIe siècles », 2011, 371p.

– Écrire la judéité. Enquête sur un malaise dans la littérature française, Seyssel, Champ Vallon, « Détours », 2015. – En toute mauvaise foi. Sur un paradoxe littéraire, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, « Paradoxe », 2015. [2] The exhaustive list of Dr. Decout’s publications can be found at http://alithila.recherche.univ-lille3.fr/index.php/contacts/decout-maxime/ |

Illinois Jewish Studieswww.facebook.com/IllinoisJewishStudies/The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studiesis an interdisciplinary program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Founded in 2009 and located within the Program in Jewish Culture and Society, HGMS provides a platform for cutting-edge, comparative research, teaching, and public engagement related to genocide, trauma, and collective memory.

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed